A short story about the importance of being integrated with the land we inhabit – from R. M. Dolin’s novel Navigating Entropy

Summary: Darwin’s a smooth moving ne’re-do-well from Chicago who recently inherited a remote high desert ranch north of Taos from is Uncle Isaac who made a fortune during the dotcom boom but turned his back on technology to pursue a self-sustaining life in the rugged foothills of the Sangre de Cristos. This story though is about none of that, rather its a two-hundred year history of the land Darwin’s decided to sell as quickly as possible so he can return to his Windy City life. Marquez Mountain is a generational story about a small patch of land that’s as rich in history as it is steeped in cultural calamities that weave their way through the importance of being integrated with the land we inhabit.

That I’ll die in the afternoon is not open to interpretation. My final fade will be along a south facing slope embraced by the sun’s last lingering kiss. They’ll find me leaning against an ancient aspen that defiantly dares to dangle on the edge of a knoll who, like a seductive dancer, successfully conceals many charms in darting glances that amplify life to the level of lore. I’ll die alone. I’m not being dramatic, just accepting of how accounts in nature need to settle up.

At least that’s how my Uncle Issac saw things the last time he journeyed up this dark and seldom traveled road. A deep dip below the old mill pond, a treacherous turn around the busted pinon, then that last long paralyzing pull up Marquez Mountain. Like an aging appaloosa that’s been rode hard and put away wet, my rust-riddled Ford begrudgingly grinds along. Every bolt, every gear, every turn of the smoothly worn crank lumbers relentlessly over the jagged cutouts and super tight switch-backs first carved out by Spanish settlers four centuries ago. Cleared by men who understood we’re all ethereally tied to the land we inhabit. Men who appreciated the way each deeply worn rut and syncopated washboard stands as poignant proof that in the struggle between man and nature, nature always prevails. Seldom can this climb be completed without needing to clear fallen trees that splash broken branches across the road, scattering needless needles around embedded boulders like drifts from a midsummer snow. Boulders that forcefully usher me into the isolated high mountain meadow I have not earned the right to call home.

My mountain meadow is an anomalous oasis in an otherwise dense forest that begins on the valley floor as a spacious mixture of Juniper and Pinon transitioning to Ponderosa part way up. As Marquez Mountain rises in ever increasing ruggedness, the Ponderosa yield to more daring Douglas Fir until all that survives along the tree line is the big bold Blue Sprue. At eighty-seven hundred feet, my mystic meadow slopes slightly east to west but relative to most mountain terrain, is remarkably flat. The lower northwest quadrant contains a quasi-permanent base camp built by my Uncle Issac before his tragic accident. The canvas tent is open on three sides and is adorned with an old wooden table full of inscriptions, many in Spanish, a mission style chair that’s at least as old as the table, a double mantel Colman lantern hung in the center, and a satellite radio. The base camp’s in the lower quadrant because it’s the only spot on the ranch able to receive Uncle Issac’s all important Chicago Cubs.

The generally oval meadow has an east-west major axis about a mile long and north-south minor axis about a half-mile wide encasing 252 acres of perhaps the most pristine pasture land in all of New Mexico. It’s little wonder one of the world’s last herds of wild mustang have been summering here over two-hundred years. A herd that locals contend contains the finest Spanish and Arabian bloodlines first developed by the last of the Marquez family. If you stand in the center of the meadow and look east, you’re awed by the grandeur of the Marquez Mountain peak rising another four thousand feet like an impenetrable fortress of jagged rock and year-round snow. Just to the south is Lost Luck Mountain; named by bankrupt miners during Northern New Mexico’s brief but colorful gold rush era. Even today geologist assert Lost Luck has all the markings of a mineral rich mountain, yet veins remain elusive. Try as they did, ill-fated miners never found so much as an ounce. That doesn’t mean Lost Luck is not without charm, only now its measured in mountain goats, black bears, and hermit beavers. Focusing past the left edge of Lost Luck, just above the tree line, one can make out the white perma-cap of Wheeler Peak in the distance; New Mexico’s only fourteener.

Marquez Mountain was briefly named Te Amo de la Montana in the mid-eighteen hundreds, by the famous southwest surveyor, Craig Stevens. The territorial Governor commissioned Stevens to draw detailed maps in a sinister effort to permanently erase legitimate links to Spanish Land Grants during New Mexico’s dark era when Protestant settlers invading from the east asserted everything they saw was theirs. Stevens ignorantly thought his name meant “the mountain that I love,” which he named for the inspiring way God shaped each wind-swept rock and carved out meadow. Convinced this meadow metaphorically represented a parting of the pine tree sea, his pious nature and Protestant dogma dictated this biblical mountain be reclaimed from its current Catholic occupants. In reality, his name translates to “I love you of the mountain.” Locals didn’t care much for his revisionist map or Anglo arrogance so over time they reasserted the mountain’s initial Land Grant name.

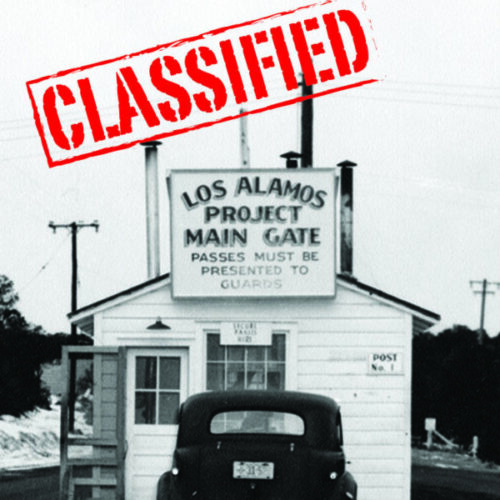

The view west from base camp is of the spectacularly panoramic Rio Grande Valley. While hard to make out from this distance, the Rio Grande river cuts an eight-hundred foot primordial crevasse down the center of the flat valley floor. Today the gorge separates mostly poor west bank Hispanic families from affluent east-siders; a demographic composed primarily of coastal retires presuming to be culturally elite, and Los Alamos intellectuals in search of a two-acre wilderness experience. At night the distant lights of Taos create a soft glow at the south end of the valley. On moonless nights the even farther lights of Santa Fe illuminate the back range of the Sangre de Cristos. Toward the north lies the Colorado border, it’s hard to tell precisely where the two states collide, but there’s no dispute it’s out there somewhere. The only town on the expansive valley floor is Questa, a dying village of predominately out of work molybdenum miners who resist the necessity to leave, but are far too proud to stay on government welfare forever. There’s not much to be had in Questa anymore, which is why I go to Red River or Taos for groceries, am in the mood for ice cream, or just need some human contact.

My high mountain meadow is encased in an impenetrable fortress of spruce dotted with small aspen enclaves protruding like white pillars of a Greek Parthenon. The aspen are open and inviting, their white trunks reach upward unencumbered before breaking out in branches rich with broad, multi-shaded leaves that present a mosaic canopy dancing daily with sunlight to the songs of the gentle mountain breeze. The foreboding barrier around the meadow however, is comprised of monster blue spruce spaced so close their long evergreen branches interlock in a titan’s chain that not only repel animals and humans, but light itself. Two steps into the spruce perimeter and the carefree mood of aspen is sequestered by cold despondent darkness, as if each step lowers you, layer by layer, through the morass of Dante’s hell. One instant the forest is alive with birds calling in a cacophony of neighborhood gossip. Squirrels chat excitedly as they jump from branch to branch in the aspen groves in a happy hurry to go nowhere. The always present breeze blows softly through the canopy creating a symphony of sounds that syncopate with the sun lightly dancing on the forest floor. Then, two steps later the perimeter world grows deftly quiet. Birds refuse to sing. Squirrels inch silently along branches with stealth precision afraid of falling. Wind perpetually attempts to penetrate the interlocked branches but to no avail. Light simultaneously attacks from the top and sides but is squarely defeated. It’s not just quiet in the blue spruce forest surrounding my meadow; it’s silence devoid of sound. An eeriness that suggests something foreboding lurks around each moss-covered tree.

An unusually large aspen grove thrives in the center of the meadow perched atop a mostly flat knoll. The grove draws unabated sunlight from the moment dawn crests Marquez Mountain until the last gasp of day is surprisingly extinguished below the Jemez Mountains on the opposite side of the valley. At the lower end of the knoll, Claim Jumper and Kismet Creeks intersect, supplementing the aspen with whatever daily rains fail to provide. Claim Jumper Creek is fed from the Marquez and Los Luck water sheds. The creek emerges from the forest at the southeastern edge of the meadow and pretty much runs down the center. Kismet Creek cuts across the meadow in a horizontal direction flowing north to south until uniting with Claim Jumper. From there, Claim Jumper Creek segues through what’s left of the meadow before disappearing back into the forest and rapidly descending to the valley floor. In Northern New Mexico, water is more precious than food, gold, or even life. Through the centuries good men have met deadly ends in nefarious schemes to acquire the rights to Kismet and Claim Jumper creeks.

The white pillared park ensconced on the knoll in the center of the meadow is where Calvin Kincaid’s homestead once stood. If you know how to look, it’s still possible to see the last remaining traces of his fireplace built from Lost Luck gold mine tailings. The granite corner stones were cut from Marquez Mountain and hewed by a mysterious Anglo on his way to California who local lore asserts was a Free Mason. The Mason spent a month at the Kincaid ranch and to this day many believe he carved out a secret cave that Calvin used to keep the cash he brought from Colorado and the gold he traded with Red River miners for meat and lumber. If you kick fallen leaves in the right places, random pieces of weathered wood that once composed the roof, or termite left-over chunks of unburned logs that once formed the walls of Calvin’s cabin can still be uncovered.

Calvin was a cowboy from Colorado who worked for Mr. Rollins, a hard but fair man who never had children. Mr. Rollins owned an expansive ranch along the foothills of the Rockies just south of Denver. Righteously religious, Mr. Rollins encouraged all his cowboys to build responsible lives. He offered to teach Calvin to read after Calvin went on and on one night about wanting to someday own his own ranch. Mr. Rollins lectured Calvin that the west was changing and in order to be successful he’d have to be both a cattleman and businessman. Calvin’s commitment to learning included carrying a copy of ‘Tales from The Arabian Nights’, that Mr. Rollins gave him wherever he went. Each night Calvin painstakingly read aloud stories of adventure, magic, love, and betrayal in either the bunkhouse or around a campfire. At first the other cowboys teased Calvin about reading romance novels involving exotic places but before long, they couldn’t wait for evening chores to end so they could find out what happens next.

Once while working on the range along with four other cowboys, Calvin read a story about a woman who was betrayed by a prince. She naively thought they were in love only to later realize she’d been tricked into becoming part of the Prince’s harem. The story talked about kismet in a way that assumed the reader understood its profound meaning. Unfortunately Calvin did not and it drove him crazy trying to figure out what kismet meant. It got so bad the other cowboys took to calling him Kismet, but it didn’t bother Calvin a lick.

Calvin was a soft-spoken easy going man with a lanky frame and wavy brown hair that never seemed to mat down from wearing a hat. Born the son of a Irish father and Polish mother who were both immigrants in New York but had to flee west to Kansas City on account of their scandalous relationship. Calvin grew up a product of the west, he enjoyed playing games, being alone hunting or fishing, and was more than capable of handling himself in almost any of the precarious situations frontier life presented.

Calvin “Kismet” Kincaid came to New Mexico in the spring of eighteen eighty-four in search of horses. Mr. Rollins wanted to breed new blood lines into his herd and learned of a Spanish rancher near Taos who had developed an amazing line known for their size, strength, endurance, agility, and heart. He was hoping to acquire eight young mares along with their newly foaled colts. Anso Marquez had spent his life on the ranch he inherited from his father and his father’s father before that going back three hundred years. Anso breed size into his horse herd using a thoroughbred stallion he bought from a Kentucky gambler who had a string of bad luck on his way to San Francisco. Anso bred in endurance using five Arabian mares a wealthy Spanish rancher sold him for next to nothing after realizing Arabians couldn’t cut cattle like a mustang. Originally the Arabians came from Spain by way of Mexico and while valued for their stamina, they were not sure-footed enough for high desert ranching. For agility and heart, Anso bred in mustangs captured along Colorado’s southern foothills, near Fort Garland.

Calvin found Anso’s modest hacienda at the base of Marquez Mountain. He had followed the Rio Grande from Alamosa, where it was nothing more than a creek, to the upper edge of the Sangre de Cristo’s twenty miles north of Taos. Anso and his wife Anna were the most hospitable people Calvin had ever encountered, after Mr. Rollins that is. They not only fed and put him up, they invited him to join them for a Quinceanera celebration at a neighboring ranch. It was there Calvin met Anso’s oldest son Carmelo who had just returned from mustang wrangling along the Colorado border. Carmelo was a strong, handsome man with an easy smile and quick handshake who captured the hopeful admiration of every eligible lady at the party. Women up and down the Rio Grande valley swooned whenever Carmelo rode by on his powerful roan stallion adorned with a beautiful black leather saddle awash with intricately tooled silver canchos.

Carmelo preferred work over parties but came to the Quinceanera at Anso’s insistence. Feminist today who all to eager to strip a men of the attributes that make them a man, would judge Carmelo harshly, but times were different then and the softness of Carmelo’s voice coupled with the dignified way he carries himself, caused women to overlook such inconsequential flaws. Wealthy fathers of marriage minded girls admired Carmelo for his work ethic, his integrity, and his ability to recognize the best breeding stock. Many had already approached Anso with offers. While not as charismatic or smooth as his younger brother Jorge, there was little doubt that Carmelo was destined for a fabulous future.

On the ride home from the Quinceanera, Anso boasted at length about how the owner of the largest Land Grant, Roberto Garcia, talked to him about Carmelo marrying his youngest daughter, Maria. Roberto had three daughters but no sons. Maria was by far the most radiant and Roberto was up front about his predicament; his oldest daughter married a man who seemed to hold such promise but turned out to be a worthless lazy drunk who lacked both character and integrity. Roberto’s second daughter married well, but at only twenty, had become a childless widow. Maria was Roberto’s last hope at finding an heir worthy of taking over his ranch. Even though Maria was only seventeen, Roberto felt she was ready to become the wife of the valley’s most eligible bachelor.

To certify Carmelo’s worthiness, Anso regaled Calvin with his feats of skill and bravery. He told how Carmelo single-handedly captured a herd of wild mustangs on the Colorado plains and culled out the very best mares, driving them all the way up to Anso’s high mountain meadow where Carmelo broke and trained them. Carmelo’s bravery and integrity were above reproach, especially after the incident last summer when four drunken Red River miners were taking way too many liberties with Victor Ortiz’s teenage daughters who were in town for supplies. Just as things were about to get ugly, Carmelo swoops in and rescues the frightened girls. In the process he kills one miner who attacked him with a knife and beat the other three so severely they never fully recovered. He then tied his stallion to the back of the girl’s wagon, and drove them home to the safety of their grateful parents.

Roberto needed a man like Carmelo, Anso argued, to give him strong heirs that would someday run his ranch. Anso explained how this exciting twist of events creates an unexpected opportunity, with Carmelo on track to take over Roberto’s place, Jorge is now be in line to inherit Anso’s ranch. Of course he’d have to talk to Carmelo about this, but why would he object? Jorge though would be a different matter, as the second son he had organized his life assuming the ranch would be Carmelo’s. His ventures were many, the latest selling gold mine claims on Lost Luck Mountain to naïve Anglos in search of wealth. The claims didn’t transfer ownership of the land, just the right to mine. This permitted Jorge a lower entry price for cash strapped seekers. He further stipulated that as the land owner, he’d receive a ten percent royalty for all gold or silver found. So far no one’s discovered a vain, but Jorge’s still doing okay for himself with contracts. Anso worried Jorge may not want the ranch, but strategized if Jorge protested, he’d remind him of his centuries old responsibility to his family.

It wasn’t in Jorge’s nature to run a ranch, maybe because he grew up as a second son, or perhaps after tasting easy money it made little logic to labor all day for far less. In contrast to Carmelo who spent his evenings at home or in the meadow tending horses, Jorge preferred the unbridled excitement of nearby Red River. Between the bars and cat houses there was always something to keep him interested. Anso never approved of Jorge spending so much time with the Anglos, but he was making money and since Jorge had to find his own way, Anso couldn’t complain.

Calvin stayed with Anso a week longer than planned because two of the colts weren’t ready for the long journey back to Colorado. During that time they went fishing along the Rio and then to Red River for a beer. One day Anso took Calvin up to his high mountain meadow where Calvin discovered Anso’s private herd. While the mares Anso sold Calvin were adequate, his personal stock was clearly superior. Carmelo showed Calvin a mouse-gray appaloosa he was grooming either for himself or for someone committed to starting their own herd. Usually cowboys aren’t interested in stallions because they’re too hard to handle, when Calvin saw this appaloosa though, he had to have him. At first Anso said no, but eventually relented after Calvin promised to someday return to start a ranch of his own. Anso vowed to help Calvin find a suitable place even though he never really expected to see him again.

Upon his return to Colorado, Mr. Rollins immediately dispatched Calvin to the Jenkins place to retrieve a group of cows who had commingled. It was a full day’s ride to the ranch and three hard days trailing cows back. Since trailing cows takes so much out of a horse, Calvin took two other horses along with his prized appaloosa. On the first night of the return trip two drifters approach Calvin’s camp just as he’s starting supper. Calvin has an uneasy feeling on account of their horses being so stressed and them being out of food but per code-of-the-west protocol is obligated to invite them to share his campfire and food.

In the quiet darkness the two drifters are stealthily gathering everything up when the older thief accidentally kicks over the coffee pot startling the still dead quiet of night. As Calvin stirs awake the younger thief panics shooting him twice in the chest. By most accounts Calvin clearly would have had died if kismet had not intervened. Turns out Calvin had fallen asleep with Mr. Rollins’ book on his chest. The drifter’s bullets slam into the book stopping just short of the back cover but nonetheless knocking Calvin out. The robbers are long gone by the time Calvin comes to. Angry and on foot, he tracks the thieves three grueling days winding up at a box canyon where the thieves are holed up. Three days of walking, of not eating, of sleeping in the cold has left Calvin in a foul mood, all that time stewing over the theft of his beloved stallion didn’t land him in a place where negotiations were likely. He didn’t even give the thieves a chance to surrender, just rushed their camp guns blazing. He shot the younger thief last shouting something about the ironic power of kismet. While gathering gear and loading the bodies, Calvin discovers the thief’s saddlebags stuffed with money. Unsure what to do, he rides back to the Rollins ranch.

Mr. Rollins helps Calvin deliver the cash and corpses to the federal Marshal in Denver uncertain what his fate would be; he did after all deservedly shoot defenseless men. His showed the Marshal his bullet riddled book of Arabian adventure as justification. As it turns out, the thieves robbed a bank in Ten Sleep, Wyoming, and not only was there a sizable reward out, they were wanted dead or alive, which meant no inquiry into the circumstances of their demise was forthcoming. Back then there was no such thing as deposit insurance so when a bank got robbed, both the banker and his depositors lost their savings. That’s why both generously rewarded Calvin. A local reporter who had just arrived in Denver from back east, asked Calvin why he didn’t keep the cash back in that canyon, after all, no one would ever know. On most levels Calvin couldn’t believe he was being asked such an absurd question but after staring down this east-coaster he simply answered, “it wouldn’t be right.”

When it was all said and done, between the bounty, the reward money, and what little had already been saved thanks to Mr. Rollin’s stewardship, Calvin had amassed enough to realize his New Mexico dream. He accepted Mr. Rollins’ offer to remain at the ranch until the following spring to undergo a crash course on modern livestock management and bookkeeping.

Falling in love with Maria came easy for Carmelo who was hopelessly lost to emotions long before plans were made for their late spring wedding. Anso and Carmelo agreed that after the marriage, Carmelo would move to Roberto’s ranch and have no time to help out anymore. Anso was of course proud and wanted only the best for his son but he was also deeply saddened that their incredibly close bond would diminish. Carmelo struggled with the guilt of leaving Anso and Anna along with the sadness of saying goodbye to his cherished meadow. He decided as a parting gesture to round up a large herd of mustangs to provide cashflow for his parents for years to come.

Carmelo ventured into Colorado finding great success. He was two days from home and two weeks from his wedding to the beautiful Maria when attacked on the flat valley floor by marauding Comancheros. The marauders waited until sunset attacking from the west to provide blinding cover in the otherwise open valley. Once they got close enough to see Carmelo’s magnificent stallion it would no longer be enough to run him off and take his herd. On most days, Carmelo could easily out run the marauders but after a full day of herding strays, his roan was worn. Realizing escape was improbable and having no place to hide, Carmelo made his stand in the open. His chances weren’t good but he hoped if he inflicted enough pain, they might withdrawal. Carmelo had already killed three Comancheros before their first bullet found its mark, two more quickly followed. Mortally wounded, he continued to fight, taking out three more before the final fatal bullet hit his heart. Falling into his last thoughts, he relived his life with Anso and Anna, pictured his high mountain meadow filled with mustangs, and saw the wonderful life he and Maria would never share.

Anso learned of Carmelo’s murder when the rider-less roan raced into the hacienda courtyard an hour after dark. Quickly organizing a search party, it didn’t take long to find the decimated battle ground. Too shocked and heartbroken to think, the search party helped Anso return Carmelo home while leaving the six dead Comancheros for buzzards and coyotes; a fittingly worthless decomposition for their equally worthless souls.

Jorge was woken early the next morning by the Madame at his favorite Cat House with news of what had happened. At first Jorge refused to believe, Carmelo was always so careful and when he got in bad situations he was so brave. After finally accepting this ugly reality, Jorge’s reaction was to go after the Comancheros and avenge his brother’s death. He was hell bent on just that when Anso intervened desperate to prevent a double tragedy. After a heated argument, Anso convinces Jorge that his responsibilities to family exceed his vengeful rage, that justice is best rendered letting soldiers from Fort Carson hunt the Comancheros down. With immense personal fortitude Jorge reluctantly acquiesces to his father’s wisdom.

Jorge arrives at Fort Carson late that morning and is informed the regiment’s somewhere around Española chasing an Apache raiding party. Rather than wait their return giving the villainous Comancheros more opportunity to slink back to Texas, Jorge decides to ride to Española hoping to intercept the soldiers. On his hurried way down Taos Canyon, he picks up fresh tracks of both hoofed and unhoofed horses understanding he’s on their trail. The Comancheros are no doubt heading to Santa Fe, the gateway back to Texas. Jorge tails the Comancheros to Embudo Station finding them in the midst of setting up an ambush where the train will stop to take on water before the long climb into Taos. Jorge stealthily positions himself in the rocks above the Comancheros predisposed to dismiss Anso’s wisdom.

In what can only be described as a random act of entropy, Jorge launches his reckoning to coincide with the Comanchero’s ambush but what neither group realizes is that the soldiers from Fort Carson are less than a mile away. Once the siege begins, soldiers race into Embudo taking up defensive positions around the perimeter. From his vantage point above the Comancheros, Jorge’s able to pick off several outlaws, including the bandit who put the terminal bullet in Carmelo’s heart. In the chaos of the moment, late arriving soldiers can’t distinguish thieving Comancheros from justice seeking New Mexicans. While Jorge’s position in the rocks prevents the Comancheros from being much of a threat, he’s fully exposed to the soldiers.

Systematically Jorge avenges his brother, each time his Winchester barks, he stoically whispers, “this one’s for Carmelo.” Just as Jorge eliminates the last of the murderous Comancheros, a well-placed rife shot from a Calvary sharpshooter strikes Jorge in the neck killing him instantly.

The first two tragedies utterly paralyze Anso, the third tragedy about to play out is less violent but equally devastating. With no heirs and little incentive to work his ranch opportunists swoop in. Anso meekly tries holding on but each time he muscles the energy to move he just can’t find the will to work. When Calvin arrives in late June, Anso’s in the final stages of liquidation. He’s sold his prized horses and is negotiating with Victor Ortiz on the sale of his land. Victor’s keenly interested in Anso’s eight thousand acres because it includes the two-hundred and fifty acre mountain pasture along with valuable water rights to Claim Jumper Creek. Two sticking points in their negotiation cause the sale to languish. First, Victor insists that Anso vacate his hacienda because Victor’s oldest daughter who Carmelo rescued from the drunken miners, is getting married and needs the house. Second, Victor’s exploiting Anso’s desperation by offering far less than a fair price.

Calvin’s unexpected arrival is an act of divine kismet. While Anso doesn’t initially believe the Colorado cowboy has enough cash to buy his ranch, he hopes to leverage Calvin’s sudden emergence to compel Victor to pay a fair price; maybe even being able to keep the hacienda that’s been in his family for hundreds of years. Calvin’s empathy and admiration for Anso is so great he eagerly agrees to pay Anso’s asking price and to allow Anso and Anna to stay on in their hacienda. Calvin convinces Anso that with Carmelo’s roan and his appaloosa they can quickly rebuild the Marquez line. Anso takes great satisfaction telling Victor their deal’s off. In a desperate attempt to secure needed water rights, Victor’s suddenly willing to pay considerably more than Calvin offered. Anso, being a man of great integrity, honors his agreement with Calvin. “There are things,” he tells Anna, “more important than money.”

Calvin quickly settles into his new ranch and centuries old community. He builds a small homestead on the aspen knoll in the high mountain meadow to keep a watchful eye on his growing herd who summer there. The big threat is bears and wolves. Bears seldom attack wildlife, but should a young colt drift off, that’s a different matter. Wolves on the other hand, have no compunction about taking a horse. Calvin chose the aspen grove in the center of the meadow for his homestead because it has easy access to water along with a view of the Rio Grande valley that’s nothing short of spectacular. By Calvin’s estimate, his life’s turned out pretty darn good. He has a beautiful ranch, is making good money selling lumber and meat to miners and lately, Anna’s been talking about her niece, Theresa, who’d make an excellent rancher’s wife.

What Calvin can’t fully appreciate about kismet though, is that all good Ying is offset by Yang; a sinister Yang that never rests. New Mexico is still America’s newest territory and even though the United States signed a treaty with Mexico stating that all Mexican land deeds would be honored, the newly Americanized Mexican citizens are learning what every other country and culture who’ve trusted American treaties has learn; namely, they can’t be trusted. Most historians assert that the blatantly scandalous land robbing era of the eighteen hundreds was about Anglos stealing land from Mexicans who they felt were racially inferior. What it was really about though was western swarming Protestants stealing land from entrenched Catholics who they felt were religiously inferior. The same phenomena happened earlier in Texas, only by the time the Protestant thieves arrive in New Mexico, they’ve perfected their craft.

Victor Ortiz lost his ranch two years after Calvin moved down from Colorado. A corrupt territorial judge with full capitulation from an equally corrupt territorial governor had declared all pre-territorial land claims null and void based on their newly surveyed maps. Then in an act of unmitigated hubris that repeated itself up and down the Rio Grande corridor, land was seized on an unprecedented scale. The generations old land owners tried to organize, but to little avail. As modern day American’s repeatedly are required to learn and then re-learn, justice for the poor and middle class in America is both blind and corrupt. The Valdez ranch on the north side of Calvin fell next to the bible quoting Judge Pearson who held public auctions for the newly apportioned land that anyone could attend. The sticky wicket though was that he held the auctions in his office without notification. With the Ortiz ranch to Calvin’s south and the Valdez ranch to Calvin’s north in Judge Pearson’s pocket, he set his sights on Calvin’s eight thousand acres and the priceless water rights that came with it.

This creates a dilemma for the zealously ambitious judge. He can’t steal the land outright like he did with others, because Calvin was an Irish/Polish American with what could be argued to be a legitimate legal claim, even if he was Catholic. It’s one thing to steal land from Mexicans or Indians, no one’s overly concerned, one could probably even get away with it on an immigrant if they’re careful. But to steal land from an Anglo American citizen would likely draw unwanted attention. The thought of paying a lowlife Catholic for land repulsed the bible quoting judge but he had no choice, so offers Calvin what by all standards is a fair price. Calvin of course refuses because he has no use for more money and he cares about what happens to his adopted family. He also feels strongly that someone should do something about this out of control corruption.

Tensions rise all summer as the God fearing judge goes about acquiring most the land on the east side of the Rio Grande gorge. But the more he acquires, the more that stinky little Polack sitting in his mountain meadow with his precious water rights eats away at the Judge. As fall approaches, he’s presented with an unexpected opportunity. Three cowboys stand before his bench facing several years in the newly constructed Santa Fe prison for doing things to a Mexican woman that would have gotten them hung had she been Anglo. The Judge offers these criminals an out; if they’ll perform a discrete task for him.

It’s not much of a decision for the three cowboys, so with minimal fanfare the Judge arranges their escape from Taos county jail. In the dead of night, they sneak up Marquez Mountain to the cabin Calvin built in the aspen grove. They set the cabin on fire and wait for the flames to engulf the structure. That’s when Calvin “kismet” Kincaid bolts out of the cabin with a pistol in one hand and a rifle in the other. He never sees his assassins, only the flash of their bullets speeding from barrel to target. As Calvin lays on the ground bleeding, his expectant bride races out of the cabin. Theresa is shot several times before reaching Calvin, collapsing beside him. Those that tell this story usually say that seeing his beloved bride dead beside him was a pain worse than death. They say that in his rage, Calvin pulls his nearly dead body upright and starts shooting at the flash flames that fill his chest with lead. There is some disagreement as to whether he killed any of his assassins on account of what happens later, but those who tell this tale like to say that with his last gasp, Calvin puts a bullet through the head of the man who shot his beloved Theresa. While there’s no way to know if that part of the story’s true, there is a certain code-of-the-west quid pro quo that mandates tragic stories such as this, end with a fitting form of frontier justice.

The bodies of Calvin and Theresa are never found. The official account recorded at the Taos County Courthouse states that Calvin sold his ranch to Judge Pearson for an undisclosed sum so Calvin could take Theresa to San Francisco for a better life. Local lore however, maintains that Calvin and Theresa are buried deep beneath the aspen grove beside Kismet Creek, that the assassins were instructed by Judge Pearson to bury them in an unmarked grave over which an aspen log was placed so that the God-fearing judge could later say a proper prayer. Legend further stipulates that the mystic Mason who carved the cabin’s cornerstones also built a stone vault somewhere on Marquez Mountain where the fortune Calvin made selling meat and lumber to miners is still entombed. Those that repeat this aspect of the legend are likely to be spotted on Marques Mountain in the summer.

The reason no one knows what happened to Calvin and Theresa is because as soon as the three outlaws escaped jail, Judge Pearson organizes a posse to hunt them down. He proselytized with profound rhetoric that any man who would do what these vermin had done to such an undeserving woman, deserved to die. He skillfully guides the sheriff and his men to the perfect ambush spot between Taos and the Kincaid ranch. Legend has it that the honorable, bible quoting, Judge Pearson fired the first shot that led to the outlaw’s one way ticket to damnation. In stories told by the posse, it’s never clear if two outlaws were killed and the third was already tied to his horse or if they killed all three. This is why many maintain Calvin got his justice.

I tell you this one of many tales involving Marquez Mountain because of the necessary way it portends the very few constants and far fewer certainties we’re allowed. It’s certain the sun will rise, at least in our life time, just as it’s certain stories need a proper ending, whether they be romantic revivals of Arabian adventure or tragic tales of people tied to their land. And even though I’m still new to this land of enchantment, I can assure you this story, at least up to this point, has the requisite code-of-the-west quid pro quo. For you see, Judge Pearson and all his fellow interlopers of similar ilk, never learn how to harmonize with the land in ways Calvin, Anso, and Carmelo could. That is why nature eventually settles the score through a host of tragic, and in some circumstances horrific, means. Call it the Ying of Yang, the age old balancing of scales, perhaps even kismet if you’re prone to the profound. But I tell you this story exactly as I read it in my Uncle Issac’s journal; a story he concluded by saying on the day he died, “Finally, I understand.”

We stumbled over here from a different web page and thought I might as well check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to going over your web page yet again.|

Thanks, can I ask how you found me?

Do you mind if I quote a couple of your articles as long as I provide credit and sources back to your website? My website is in the very same niche as yours and my visitors would certainly benefit from some of the information you present here. Please let me know if this okay with you. Many thanks!|

Absolutely. My goal is to get information out so feel free to reference me all you want. Also, I always appreciate feedback.

Thanks