Chapter 4 of the R.M. Dolin novel, "Trophic Cascade"

Read companion poem

Long past midnight, after fierce Santa Anna’s rest and the May moon descends, Jake toils in solitude, processing malted mash into Mula. He has a semi-annual commitment to keep, and the Quintana Brothers are stopping by tomorrow to collect. Chance offered to help, as did Dario, but making Mula is off the books so Jake can’t really involve them. If Revenuers find out prohibition era Mula is once again being made in the mountains of Northern New Mexico, their punishment will be swift and harsh. Jake’s okay working alone, its’ one of the ways he spends time with Emelia. She was after all the one to start their distillery. First, she only wants to open a winery but sees how bored Jake is so suggests they branch out into distilling. Emelia has an amazing way of knowing what Jake needs to stay on solid footing, she’s acutely aware of his need to keep his mind and body constantly active; nothing good comes from him being idle or left alone with his thoughts.

Jake divides life between the good he’s done and the bad he regrets; between happy memories and those no longer possible. Like all of us, some memories provide satisfaction and amusement alongside those containing deep torment. If compelled to sort his memories into some sort of cascading order, he’d put bad and stupid before the sad and forlorn, and all those combined boil into his consciousness more often than happy.

Once his Still’s loaded and the boiler heated, distilling pretty much comes down to watching gages, checking the outflow, and knowing when to switch between heads and hearts, and hearts and tails. The process takes all night, which is perfect since he and Emelia have a lot to work through. Given everything going on with Sympatico, Miguel, and now this new guy Alvarez, there hasn’t been time for anything other than right now. Probably why Jake’s been thinking a lot about his life’s journey to right now. Probably also why Sympatico’s timing is flawless.

“Senor Jake,” she says stepping into the distillery with a tray of coffee and cookies, “I brought you treats.”

Jake helps her set the tray on a workbench beside the Thumper. “Thanks, that’s very kind. And again, it’s just Jake.”

“My coffee is not as strong yours, but it’s too late for strong coffee. The cookies are oatmeal.”

“That’s my favorite, how did you know?”

Sympatico fills two cups from the carafe. “You have eight boxes in the pantry.” She walks over to the copper Still to listen to the melody of creaking and cracking as the metal and mash warm up. “It sings like a kettle on the stove.”

“Have you ever seen a distillery before? The chemistry’s simple, but the setup’s complex.”

“No, Bolivians drink Pisco, but that comes from Peru.”

“I know Pisco, not Bourbon but not bad.” Jake steps back “I designed and built all of this, the Stills, the Thumper, and of course the Worm. The stuff coming out now is methanol, it’s the same pure poison found in beer and wine that distilling takes out. Four ounces of methanal kills you, two makes you permanently blind the little bit in beer and wine is what causes hangovers. Once the methanol’s out, the ethanol starts. That’s the happy alcohol. There’re three phases to an ethanol run: the heads, heart, and tails. The heads still have some methanol, so we don’t keep that. The tails have too many volatiles that ruin the taste, so we don’t keep that. In between are the hearts, the good stuff. The art of distilling lies in knowing when the heads, heart, and tails start; and of course, in not being greedy.”

“You must be very smart to do all this.”

“I had help. I wasn’t always a distiller, ya know. I used to be many different things; some good, some bad, but each bringing me here. That’s how life is ya know. When I was twelve, I got in some trouble and was sent to work on a ranch for two years. You learn quick on a ranch about the harshness of life. Nothing bad happened, still though stuff shapes ya. Things like separating your shoulder getting bucked off a horse or getting cut up stringing barbwire.” He rolls up his sleeve. “Got this when a wire I was stretching broke. The recoil wrapped around my legs and arm cutting all kinds of gashes. Can’t show you all the scars, at least now without embarrassing myself.”

Sympatico looks at the large scar running the length of Jake’s left arm, “it must have hurt.”

“Not as bad as the time I was bucking hay bales and got bit by a rattlesnake.”

“Oh my God!”

“Can’t show you that scar either. It was hot as hell, and we just baled the third cutting. I didn’t see him coiled up on the sunny side of a bale. Luckily, I was wearing leathers, which I rarely wore, but those bales were full of thistle and the thorns tearing right through my jeans. The rattler sprang at me so fast I only had time to turn a bit, exposing the one place my chaps didn’t cover. They say he would have killed me had he hit muscle. Instead, I kill him. The Foreman cooks the poor bastard for dinner, says it shows respect and honors the eternal roulette wheel of life that chose to spare me. I still have his rattlers on my dresser to remind me how fragile life is and how quickly unexpected crap comes at you. The thing is, whether you live, or die depends on fate more than meticulous planning or careful execution. And crap never stops coming.” As Jake pauses to reflect, Sympatico senses the moment needs no response.

“There’s lots of lessons from my cowboy days. During calving season, every day brought unimaginable sights, horrific smells, stuff that’s forever etches into your psyche. You learn the callous objectiveness that life and death consume with equal gusto. And the only way to put it in any kind of context is to say, ‘it’s necessary’. As soon as calving season ends there’s branding and cutting, most ranchers tag their cattle now, but in my day we still branded. The stench of burning flesh as a red-hot iron presses into service is flat-ass disgusting. But as bad as that was, the male calves were about to discover an even more horrific fate. Once caught and rolled on their side, my job was to press a knee against the frightened animal’s ribcage until after the brand was applied; then I’d grab both hind legs and hold them apart as the Foreman, with surgical precision, swoops in and converts the future bull into steers. Most times the calf could only kick me once or twice before the deed was done. By time we’d finish going through the herd, I’m covered in bruises.”

“That horrible.”

“Yeah.” Jake gets up to check his gages and measure the methanol. “Life’s hard. Even when all you’re doing is trying to survive below the radar it keeps coming at you.” Jake dumps the bucket of methanol into a 55-gallon drum. “When I graduated eighth grade, I felt I was done with school and ready to make my way. Dad thought it was reasonable, but mom was like, ‘Hell No!’ The thing is, I didn’t much like school. I was bored, always in trouble, and it seemed there was this wonderful wide-open world needing to be discovered. Mom insisted I finish though; said she wanted her only son to have a shot at life. It’s mom, so what can I do? As a partial compromise, dad gets me a part-time job with the local plumber. As things turn out, that’s exactly what I’m supposed to be doing at that moment.”

“So that is where you learned all this?”

“It’s where I learned to fabricate metal, designing skills I taught myself.” Jake makes some notes in his logbook, does a quick calculation on his laptop, then sits down beside Sympatico. “Methanol run’s almost over.” He takes a cookie. “These are mighty fine, Ms. Sympatico. I like that you added walnuts and raisins, just like-” Jake abruptly stops.

“Like Emelia used to do.” Sympatico finishes knowing she’s touched a nerve. Her admiration for Jake grows each time he struggles with his sorrow. It reminds her so much of her Abuelo. “I found the recipe in a box you keep in cabinet.”

“Thank you,” Jake manages to say. “It’s perfect for a night like this.” He takes a moment to regain his composure. “I wasn’t just a plumber; I also rode bulls in rodeo.”

“No.”

“It’s not as crazy as it sounds. On the South Dakota rodeo circuit most riders are in their teens or early twenties. I was on the younger side but held my own. I tried bareback and saddle bronc but quickly realized the distance of the inevitable fall was a lot higher on a horse than bull. Other positive parts of bull riding are you don’t have to mark the animal out of the chute, and the rowels of your spurs are locked so you can use them to regain position during the ride. It’s kinda cruel, but when you start to fall to one side, you dig your spur on the animal’s other side into his hide to pull yourself back up, which of course just fuels the rage he already has.”

“I don’t think I could watch such a thing.”

“With horses the rowels on your spurs spin freely, but you have to mark the animal out of the chute; that means racking both your spurs along the horse’s front shoulders during the first buck. If you miss your mark, you’re disqualified. On the flip side though, a horse does everything it can to avoid kicking or stepping on you. A bull, however, delirious with rage, thinks of nothing but kicking, stomping, or goring you. Saw a lot of good cowboys get busted up. One night, this bull kicks a guy so bad in the face he bites off his tongue. I never got hurt, not seriously anyway; I mean I could show you some scars, but I always was able to walk away. Another time this cowboy gets stepped on so hard his heart stops. A couple times I came close to something serious but always managed to escape. My worst injury was during a Friday night ride when my bull got spooked just as I was setting up on top of him. I just get cinched to this Brahma bad boy in a way that won’t break my hand when his bulging bump gets to moving around during the ride. Then suddenly, and with great purpose, he hops up on his hind legs and tries to jump over the wooden rails. This angry, frightened, highly determined beast was about to fall over backward in a move that would have crushed me. Luckily, the alert Chute Boss opens the gate spilling both me and the pissed off bull into the arena. The bull’s so disoriented he spins around inside the chute and before bolting out in the wrong direction scrapes me along a gate post tearing up my shoulder pretty bad. Took weeks to recover but like I said, at least I walked away.”

“Why would you do something so crazy?”

“Why does a man do anything, for glory and to impress the ladies.”

“Is that why you’re helping me?”

Jake takes a bite of his cookie and a sip of coffee. “A man starts out bold, stupid, and invincible. As he matures, he’s motivated more by doing the right thing. The irony of my busted shoulder was that the entire incident, from the time that bull gets spooked until he slams into the post, lasts no more than one, maybe two seconds. During the whole ordeal, there’s nothing I can do to alter outcomes. I’ve watched lots of other cowboys go down with the same irony. It really is true what they say, ‘but for the grace of God go I.’”

“I’m beginning to understand why you still risk so much for so little.”

“Rodeo is the only true professional sport, the only real measure of a man. In baseball, basketball, football or soccer, players get paid whether they perform or not. In rodeo you either win or go home broke and busted-up. On top of that, each cowboy has to pay for the privilege of competing. If you ask me, professional football players are the biggest pansies in sports, they have so much protection and play so few moments during a game there’s no test of courage or endurance. In a sixty-minute contest, offensive and defensive players, average thirty minutes. If each play lasts seven seconds followed by a forty-five second rest period, a player is only engaged two-and-a-half minutes per game. Of that, a play comes their way say one in eleven times. This means they’re on the job seven seconds per game. In bull riding, a hundred-and-sixty-pound cowboy battles a two-thousand-pound bull who doesn’t want to simply prevent you from gaining yards; he wants to kill you. And the only protection you have is your ability to outmaneuver and outwit him. Sports would be much better if participants got paid based on performance. If a running back didn’t get paid when he fumbled or failed to rush for a hundred yards, there’d be far fewer fumbles and far more hundred-yard games.”

“My abuela would talk like that when his football team lost a match.”

“Rodeo’s hard and demanding. A typical season stretches from Memorial Day to Labor Day. I’d get off work early each Friday and find my way to whatever town was featuring a rodeo that night. After my ride, I’d drive to the next town for the Saturday show. Usually, I’d stay the night to attend the rodeo dance or get drunk in a bar. Unfortunately, both activities usually lead to fights, although for different reasons. On Sunday morning I’d either wake up in my truck or in the arms of someone I fell in love with for the night. I’d be on the road early enough to make the next town in time for their matinee. After my Sunday ride I’d haul my battered body home in time to be at work on Monday. I rode with three other cowboys; our rule was if you aren’t at the departure spot in time you have to figure your own way to the next town. I got pretty good at hitching rides and negotiating transportation with girls I’d never see again.”

“Well,” Sympatico huffs, “it is good to find out now that you are like every other man!”

“The me back then maybe, a little, but he still had a lot of growing up to do. The lessons of rodeo, beyond glory, are that risk gets rewarded. That a man has to face his fears with calm courage and be prepared to pick himself up after falling. The thing is, all men fall. It’s because God gave us a poor sense of balance. Nobody owes anybody anything, that’s another lesson you learn from rodeo. To survive you must continually prove yourself, to yourself, while telling the rest of the world to go to hell.”

“I will believe for now that you are, as you claim, a fallen man who rose up better.”

“Thanks, I think.” Jake can’t decide if he should continue his story. The way things have gone their past few interactions, he may be wise to cut his losses but that’s not he cloth he’s cut from. “I eventually do graduate high school, and even though I finish seventh from the bottom, it doesn’t matter. What matters is I kept my promise. It didn’t matter to mom either, she just wants me keeping my options open so that when I figure out where I’m supposed to be, I have the ability to get there. My guidance counselor said I should find work in the trades, so after high school I continue working as a commercial plumber. I live full time on the road in uninspiring places like Worland, Wyoming or Brainerd, Minnesota but life is good. By the ripe old age of nineteen, I’ve been on the road two years and find myself standing knee deep in freezing ditch water in Ashley, North Dakota as blistering cold Canadian wind blows January snow at me in a blinding wall of white. It’s then I decide this was not something I want to be doing at fifty; so, I quit.”

“Just like that?”

“Once you realize the way things are, are not how they ought to be, it’s illogical to spend even one moment doing them. Constant change is both necessary and good, even when it involves radical action. So, with my rodeo days retired, my plumbing career in the crapper, no pun intended, I wasn’t sure what to do. That’s why I don’t dismiss mom’s suggestion I go to college. She has an amazing wisdom, but this has a touch of crazy. Never, under any circumstance, did I consider myself college material. I wasn’t one of those kids recognized early as brilliant and encouraged at each step of their academic development. If high school transcripts are any indication, I wasn’t rich with latent potential either. But then again, out of work and out of ideas, maybe college isn’t a bad place to hide from life, and who knows, maybe I’ll even meet some pretty college girl.”

“I see maturity hasn’t hit yet.”

“Probably not, still hiding and chasing, hiding from responsibility and chasing glory. I hadn’t met Emelia yet, the person to teach me the profoundness of life, about love and how to love.”

“I was supposed to go to college.” Sympatico reveals. “My Abeulo, was an engineer, and his dream was I follow in his path. But then-,” she pauses to find fortitude. “What happened, happened.”

“You’d be a great engineer, certainly better than I started out. When I go to get my high school transcripts, my principle laughs at the thought of me in college. He mocks me even more when I tell him I’ll study engineering. First, he says they won’t let me in. Then he says even if I get in, I won’t last a semester. While not fun to hear, he’s right, there’s no way I’m prepared for what was coming. Today I wouldn’t get in, but back then South Dakota was an open enrollment state, which means residents are automatically accepted in any state school. Since I was already living in Rapid City, I applied to Tech. When the adviser asked what I wanted to study, I didn’t know but mentioned I’d worked several years as a plumber, so we settled on mechanical engineering. To be honest, I have no idea what an engineer is but know me and my construction buddies hate them.”

Jake starts the process of switching the distilling run from the poisonous methanol run to happy ethanol. As soon as he does, the distillery aromas transition from harsh and bitter, to soft a floral. “Of all the years I spent in college; four for my undergraduate, one for my Master’s, and two for my PhD, my absolute hardest was freshman year. When I promise mom I’ll finish high school, we don’t negotiate a curriculum, so I spend four years taking classes in woodworking, agriculture, electrical wiring, and machining. My first lesson in college involved the principle of zero-sum game. Four years of goofing off in high school had to be made up, which was very humiliating. First, I was older than the other kids and my life experiences made me even more mature, even if you don’t think so. Second, while my classmates were taking standard college courses, I was stuck in “pre” courses, pre-calculus, pre-physics, pre-chemistry. From the time my journey to right then began, starting at the ranch when I was twelve, workings as plumber, living the hard life of a rodeo rider, it was all to prepare me for my first semester. The entire time I felt like all I was doing was falling, deeper and deeper into a pit with no way out. Concepts and ideas coming at me so relentlessly my anemic brain couldn’t take it.”

“But you stuck it out?”

“Hell yeah. It’s embarrassing to be nineteen and working my ass off to get C minuses in what amounted to high school courses, but the thing is, I never felt stupid, just uneducated. I never thought I couldn’t do it, I just sometimes questioned if I had enough endurance to pull through. I learned something important about myself and the world at large, there’s a lot of highly educated people who are flat-ass stupid, while some of the smartest people I’ve ever met didn’t finish high school. It’s like dad always says, ‘a college degree and a buck-ninety buys you a cup of coffee, if you drink reasonably priced coffee.’”

“You are lucky to have such amazing parents, I never really knew mine. My father died in the gas workers protests then mom died of a broken heart. I believe they were amazing people because my Abeulo would tell many stories about their bravery and love. The world would be so much better if more people like them could survive. Sadly, this world is not meant for such souls.” Sympatico wipes tears from her eyes, tears containing memories she long ago buried in the deepest recesses of her being that were then covered by years of torment. “Please,” she struggles to say, “continue your story.”

Not sure how to restart given his story seems small and inconsequently compared to hers. At the same time, he sees she needs a distraction to pull her back from darkness, and what better distraction than the meaningless story of Jake. “My second semester wasn’t any easier, only I managed to get my GPA up to a C average, enough to remain eligible to stay at Tech. My sophomore year was still a struggle but slowly, things were coming easier, and my GPA moves up to a high C. By Junior-year, everything clicks, and I uncover an ever-increasing ability to comprehend complex material. That, coupled with the incredibly intense study habits I’d developed during my first two years of struggle, quite unexpectedly propels me into being one of the best students in any class I take.

“By the time I graduate my GPA is up to 3.5 and I’ve been on the Dean’s List four straight semesters. But even with all that success, the thing I understand more than anything else, something most of my peers never will, is I know what I don’t know, so now my quest for knowledge is insatiable. That’s how I end up in graduate school. After taking the Graduate Record Exam, I’m getting invitations from places like Case Western Reserve, Rice, Georgia Tech, and Stanford, all top tier programs. But like a naive schoolboy, I pass on these schools choosing instead to attend New Mexico State; mostly because all those other schools were in large cities, and I can’t imagine being able to think in a crapped-out city. Also, a Professor I respect tells me Las Cruces is ‘just like the Black Hills.’

“I’d never been South of Denver, and since Denver’s pretty much like the Black Hills, I blindly believe New Mexico will be too. That damn Professor’s practical joke became my first experience with the demented form of humor New Mexicans are famous for. I arrive in Las Cruces at dawn after driving all night and as the sun comes up over Mesa Valley understand in no uncertain terms, I’ve been had. Rather than the wilderness forest I’m expecting, before me lays a barren wasteland. However, as uninhabitable as Las Cruces is, the thing State has over the other schools is they’re at the forefront of an emerging technology called computer-aided engineering. I know enough about computers to know they’re the future. But the real, pièce de résistance, is they offered to pay my tuition and give me a five-thousand-dollar stipend. I didn’t know what the hell a stipend was, other than my days of being a poor were over. The thing I won’t realize until years later is all those other schools were offering the same package, they just took for granted I’d know that. But how could I? I was from a world where men are expected to pay their way, so who would have thought universities pay engineers to go to graduate school? It had to be fate, only that explains why I passed on far more prestigious schools to study on an obscure campus in the middle of a desert wasteland.”

“I was in Las Cruces-, before Santa Fe-.” Sympatico takes a moment to once again regain her composure. “So, that how you came to here?”

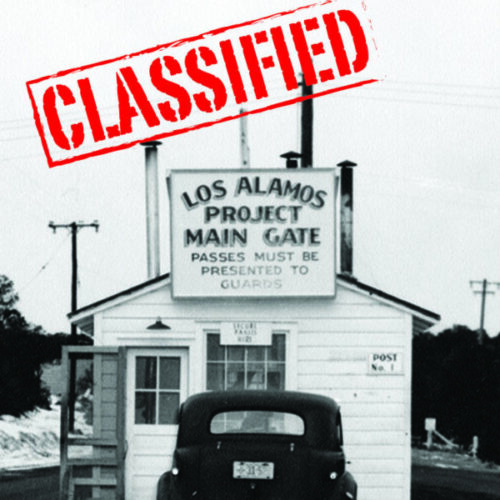

Jake’s is once again uncertain if his trivial life story is worth continuing when what she’s dealing with is far more profound. Lacking any better ideas, he presses on. “Most of my peers were recruited by IBM, or Sandia. For some reason Los Alamos takes a shine to me, which is ideal because, not only is Los Alamos the most prestigious research center in the world, it’s also a small mountain town that really is, ‘just like the Black Hills.’

I start as a summer intern after my first year at State. The Group Leader sits me down with two other interns: one from MIT and the other from Berkeley. He boldly announces that at the end of summer one of us will be offered a full-time job. I’ve been around the block enough by now to know South Dakota cowboys with an anti-heroic GPAs don’t compete well with the likes of MIT or Berkeley, but at least I’d have the experience to put on my resume.

“What I have yet to fully realize is that there are two kinds of genius, those with natural talent and those who work and struggle. While I’m from the latter camp, my competition journeyed a much softer road. I also don’t appreciate that being successful at Los Alamos requires more than book smarts. By the end of summer, I simply out worked my rivals, out delivered on our technical tasks, and along the way demonstrated that rarest of talents an intellectual can possess; being both technically skilled and creatively imaginative. I accept their job offer and stay in Los Alamos completing my Master’s in absentia, happy to put Las Cruces in the rear-view mirror. So, at the ripe old age of twenty-three, I begin my career as a nuclear weapons analyst, a fate-filled journey that started at twelve and took many circuitous detours before finally delivering me where I’m supposed to be.

“By extension, that’s how your life and mine intersect; you don’t start out to be here, don’t make plans to be here, don’t execute a grand strategy. You have plans to be sure, like going to college in Bolivia. Fate though, that pesky gremlin steering our lives from obscure shadows, has other ambitions. Now here we are, each with a story. What’s in a person’s rear-view mirror matters little when going forward, other than to remind us of the lessons we’re meant to learn. What matters is that we go forward. While I can’t help but wonder with awe, what fate has in store for us, I also accept without question that here is where you and I are both supposed to be.”