Chapter Three from the R.M. Dolin novel, "What Is to Be Done."

Read companion poem, Read original poem

The Al Azar’s charm is situated a mile off a desolate segment of highway between Española and Santa Fe, just past the turnoff to the high road to Taos. The quasi-paved road is something of an anomaly because it’s lined on the acequia side with native cottonwoods and on the other side with intrusive Chinese elms. No one really knows how the alien elms established a toehold, but everyone’s certain they’re not leaving any time soon. Positioned along the private property side of the Nambe River, the boot-brown hacienda was built using adobe bricks from Chimayo mud baked in the hot August sun by Armando’s great-great-grandfather. Calling the Nambe, a river is high desert sarcasm since it only flows during spring runoff or after intense monsoon rains. The Al Azar lies in a reasonably flat portion of the narrow valley but rising up on the opposite bank is an imposing juniper dotted mesa that hosts the recently opened Wind River Resort and Casino. Unlike other Pueblo properties, the Wind River is upscale, targeting affluent Los Alamos intellectuals, bored Santa Fe trust-funders, and deep pocket tourists hanging out in Taos.

“Unfortunately,” Armando’s fond of saying, “money’s not like shit, it doesn’t roll downhill.”

At first locals welcomed the high paying casino jobs provided by the Pueblo’s exploitation of reservation duality. “Finally, an industry not beholden to nuclear weapons.” Over time though, most came to lament the cascading consequences. First came the mobile homes, then came the people who live in mobile homes. The influx of easy money changed even life-long residents as crime and drug abuse skyrocketed. Folks now lock their doors mindful not to leave things in their yards or cars, and old timers readily concede building bombs brings a better class of people to the valley.

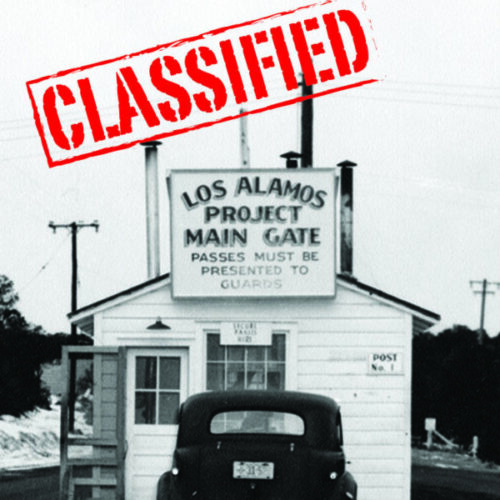

Locals mostly don’t mind eccentric Los Alamos PhDs, even though some struggle to reconcile the Laboratory’s mission. What offends them is these intellectuals, who first arrived during World War II’s Manhattan Project, make no effort to assimilate. Los Alamos remains an intellectual oasis like no other, a cosmopolitan community of the world’s most gifted engineers and scientists so immersed in lofty thoughts they have no time to develop a culture of their own, let alone assimilate to the centuries old one they’ve encroached.

“I should hang a sign,” Armando constantly threatens. “No Trailer Trash. No Trust-Funders. No Tourist – Labies welcome with Adult Supervision.”

The Al Azar is a reasonably rectangular structure that’s stayed open in defiance of the Governor’s lock-down orders. It has surprisingly square corners, possibly plumb walls, and large plate glass windows in front accenting both sides of a traditional New Mexican blue double door. Each window runs from knee high to the just below the ten-foot ceiling and is six feet wide. A single rough-cut timber supports the flat roof over both windows and door. Armando’s great-great-grandfather started a tradition by carving his name in the timber just above the left corner of the left window. Beside that he carved a poem professing his eternal love for Magdalena, the wonderful woman who somehow found a way to love him despite all his irredeemable failures. Each generation has since marked ownership of the Al Azar in similar fashion. Over the right corner of the left window, Armando immortalized Maria and their five kids in a whimsical poem that, relative to his ancestors, is a bit long and melodramatic.

Between Armando’s Dad and Grandfather’s inscriptions, someone carved, “Outlaws Forever, Never Captured, Never Diverted, 1959.” While no one knows for sure who carved it, most assume it’s paying homage to the night federal Revenuers, attempted to ambush Ernesto Quintana as he made his infamous Mula run along the high road to Taos. Ernesto not only outran and outmaneuvered the federales, he completed his run in record time without breaking a single bottle. Over the blue door is the boldly carved inscription, “Through These Doors Pass the Brave and Bold Who Recklessly Challenge both Nature and Authority, 1917.” Soon, Armando threatens anyone who’ll listen, his oldest son will proudly add his inscription. It will be the first one over the right window signaling the start of a whole new Al Azar era.

The massive adobe walls are twelve inches thick and while the interior’s plastered white, obvious color variations highlight the continued lack of success roof repairs have had. The floor is tongue & groove oak laid on top of dirt. The oak’s badly worn in front of the door and along the bar but reasonably good elsewhere. Armando knows he should replace the worn boards but rationalizes that they haven’t deteriorated much since he took over and the next owner is better equipped to deal with it. Lacquerer that gets added to the floor every few years has darkened the oak to a burnt black sheen.

The ceiling’s held up by massive Ponderosa vigas making the room seem deceptively small. The vigas were harvested from the Jemez Mountains just west of where the South Fork flows into the Valle Calderas near the open meadow that lost most it’s trees twenty years ago in a lighting fire. The vigas support an elaborate roofing system that’s something of a metaphor for southwest complexity. The first roof is tongue & grove boards over the vigas that are covered with two feet of dirt and is over a hundred years old. Ineffective against rain, someone laid 2×4 stringers on top of the dirt and covered them with plywood, asphalt, and gravel. That roof didn’t hold up to heavy Monsoon rains so two years ago Armando installed a raftered propanel roof over the gravel. After years of water staining the Al Azar’s white plaster walls, the red metal roof seems okay, but since Armando did the work, there’s a running wager as to how long it’ll last.

Jake implored Armando to remove the old roofs before adding the rafters utilizing an array of engineering arguments. He now pauses before entering to calculate the weight each viga is expected to support coupled with a deterioration factor for 123-year-old logs to arrive at today’s probability of collapse. As he pensively journeys under the inscription carved timber, he convinces himself, “probably not today.”

Al Azar in old Spanish means chance, as in game of chance rather than chance encounter. Of course, Armando always caveats, “it is perhaps a double entendre, Cabron.” As the Al Azar’s only bartender, Armando, opens when he gets around to it and closes whenever something more interesting suggests his attention. Armando’s grandfather made the Al Azar famous as the distribution hub for the Quintana Brother’s illegal liquor enterprise that started during Prohibition and operated openly into the nineteen-eighties making it the last remaining remnant of those lawless days. Armando artfully avoids answering questions about his bar’s history. “If you need know, Cabron, you already do.” While the same age as Jake, Armando is, at five foot eight and two-hundred and forty pounds, shorter and noticeably rounder. Jake cycles regularly to stay in shape, but Armando leads a more sedate life sustaining himself on domestic beer and traditional Northern New Mexico cuisine; a staple rich in lard. His thick silver hair has a playful waviness that ironically helps him seem young and charming.

“The boys’ll be here soon,” Armando quips while mixing a fresh cocktail.

Jake surveys the empty bar lamenting the feigning solitude. “I thought you were nuts suggesting we play in defiance of the Governor’s mandate but applaud the stand you’re taking.”

“Screw the Governor and her dumb-ass mandates!”

Every Thursday, Jake, Armando, and the rest of the ‘Americans for a New America’ (ANA), gather at the Al Azar. Comprised of retired Los Alamos intellectuals, their name was coined by Jon, based on the group’s overindulgence in psychoanalyzing everything wrong with local, national, and world affairs never short of knowing who to blame and exactly what they’d do to set things straight. There’s some disagreement as to exactly how things went down, but they tacitly concur that one night, in the midst’s of a particularly heated debate, Dwayne concludes, “somebody’s gotta do something.” To which Armando whimsically observed, “it’s our fault I suppose, we elect stupid people to feel better about ourselves.”

From there the discussion devolves until Jon summarizes their sentiments by asserting that given their unique lineage, it’s their responsibility to set things straight and somehow that assertion becomes the catalyst for the path they’re currently on. The boys weren’t always subversive, in fact, twenty years ago at the height of the Mind’s Eye Project, they were polar opposites. Jake, Preston, Dominic, Jon, Theo, and Dwayne were recruited to lead a newly launched government project requiring super-secrecy. The Soviet Union had just collapsed, and the nuclear test ban treaty was a year from ratification, politically and socially the world was immersed in an unprecedented state of chaos. The Internet age was mushrooming and with it, unintended transformations cascaded through countries and cultures in ways no one foresaw. Government paranoia coupled with their struggle to figure out how to control the chaos, or least constrain it, caused them to consider all kinds of crazy proposals, including Jake’s Mind’s Eye idea. Then came 911, and Government’s manic hysteria manifested in funding the project with extreme pressure to quickly produce results.

The boys played poker to decompress from the relentless intensity with Armando not joining until after the project’s canceled. For obvious reasons, he quickly became the game’s standing host. Armando and Jake met while collaborating on a research project in the plutonium facility to develop new ways to manufacture weapons grade materials with less radiological exposure. Jake needed a skilled machinist, but Armando was reluctant to participate, like most PhDs, Jake’s way too driven for Armando’s casual refinements. Ironically, when Armando exceeds his dose limit halfway through the test suite, they have nothing to do until his dosimeter account resets but hang out and talk and from there they just grew on each other. Two years ago, Dario joined, again on Jake’s recommendation. It’s never been clear how Jake and Dario hooked up but Dario’s the group’s anomaly; not because he’s Hispanic or a veteran, but because he’s in his forties, still works at the Lab, is a quasi-professional poker player, and brings an edginess to the ANA they didn’t even realize was lacking.

Like thousands of loosely formed groups of old men in bars, coffee shops, and cafés across the country, the ANA debate and dissect current events never short of knowing who to blame and what should be done to fix things once and for all. What makes the ANA unique is not so much the passion they bring to the discussion, but the level of insight they provide both problem analysis and solution. It’s as simultaneously impressive as it is worrisome to people who sit in super-secret government centers carefully watching such people. If the Watchers ever get wind of the ANA, warning sirens will reverberate through governmental surveillance centers around the world. This is why Thursday night poker is cloaked in secrecy; something routine for these former nuclear weaponeers.

“Hope Dario makes it,” Armando offers while cracking the seal on his second cerveza. “I need a homie to balance out you brainiacs.”

“He’s coming,” Jake laughs, “got banned again at the Wind River so he’s got nowhere else to be.”

“What can I say, Cabron, we Hispanics are passionate people.”

An ordered procession of headlights suddenly illuminates the otherwise dark room splashing down the bar before dancing along the back wall, their searching strobes bobbing up and down with the harmonic rhythm of tires bouncing in and out of potholes that never seem to get fully repaired.

“Do you know what happened?” Jake asks.

“Punched a guy,” Armando answers as if it’s no big deal. “This brother from Ohio loses half his chips on a poorly played hand and blames Dario. Mr. Ohio, insults Dario’s mom, which causes Dario to go old-school on his ass. It might be okay back east to insult another man’s mom, but here in God’s country, Cabron, any man would have done the same.”

“Apparently.” Jake surmises while looking toward the door. “He only got a week suspension. That’s of course on top of his year-long ban at Tesuque.”

“True dat.” Armando quips, pleased to use the expression his grandson Benito taught him last week at his nephew’s birthday party held in rebellious defiance of the governor’s quarantine and mask mandates. “He is running out of casinos though.”

Jake saunters to the front window gliding his hand along the white plaster wall tracing the tactile waviness caused by each generation’s attempt to make the Al Azar new; each trawl scratch quietly trying to explain the difference between the underneath of all that’s lost and freshness of what’s still to come. He wonders how his life would be captured in plaster; how it would be different absent that one tragic night. He feels the cold air coming down from Colorado move unabated through the drafty bar in eerie echoes of emptiness, as if every bone that ever breathed within these walls were trying to say something.

The PhDs burst into the Al Azar followed by two Mexicans who pause in the entryway to discern how their presence is perceived. After confirming the rumors, they grab the first two bar stools. Preston bounces behind the bar grabbing their private beer stock from the glass cooler as the rest of his cohorts assume their stations.

“Customers,” Jon sighs looking at the Mexicans. “Given the latest mandates from Fräulein Fuhrer, I thought for sure we’d be uninterrupted.”

“No ANA tonight,” Dominic concludes.

Theo swoops up the loose pile of cards scattered around the table assessing if any might be missing. “Just as well, poker on Cinco de Mayo is ominous enough already.”

“That’s what I’m saying.” Jake eagerly interjects taking his usual seat.

“So, you heard,” Dwayne grouses, plopping his large frame into a seemingly small chair. “Impressive, even if scary.”

Jon smiles sarcastically at Preston, “and you said no way.”

“I didn’t say it couldn’t be done, I said it wouldn’t be done.”

“When the bodies start piling up,” Dario states, “it’s a difference without distinction.”

Dwayne stares at Jake with a dueler’s intensity, twisting long strands of orange whiskers. “We have to fix this.”

Jake’s searches for tells, but like good gamblers, each player conceals any concern. “Yeah, this one’s definitely on us,” he concludes.

Armando slides down the bar toward his customers. “Strange you boys be out given the latest mandates.” The two Mexicans scramble to attach their dust-stained face masks. “This bar is a mask-free zone,” Armando declares.

The older Mexican, tentatively lowers his mask, “what about government orders?”

Armando gestures toward the poker table. “See those Anglos, all PhDs from Los Alamos, they ain’t wearing any stinking masks. If they think masks are meaningless, who are we to argue. So, what can I get ya?”

“Dos cerveza Corona porfavor,” the older Mexican states, pulling a twenty from his shirt pocket and pressing it flat on the bar to prove in advance he can pay.

“Not out celebrating?” Armando quips reaching into the beer cooler. Of course, he speaks fluent Spanish, but as a matter of policy, only talks English to Mexicans; otherwise, as he likes to lecture, “how will they learn?”

“Your holiday not ours,” scoffs the younger Mexican.

“True dat,” Armando concedes with a gregarious smile.

Both Mexicans are small in stature and from their worn appearance could be related. What marks them as migrants is foremost their complexion, which is darker than a Northern New Mexican Hispanic. Their cowboy boots are longer and more pointed than their American cousins with an upward curl at the end. Their colorful belts with huge buckles, and straw hats creased in dramatic ways no American cowboy could bring himself to do are other obvious indicators. The cut of their jeans and the dusty sweat-stained western shirts further highlight their origins. Armando concludes they’re probably from central Mexico and came north for chili planting or to clean acequias.

Applying skills passed down through generations, Armando tosses a fresh lime onto the counter efficiently cutting it into quickly equal quarters. He presses a wedge into each bottle before setting them on the bar, and taking the twenty to the cash register, he returns with a five, and five ones. Mexicans rarely tip but Armando is, if nothing else, an optimist. As he starts for the poker table, the door squeaks open allowing a frigid blast of cold Colorado air to burst into the already dank room. With great effort on account of his limp, the old man who moved into the Valdez house two months ago, manages to close the door and shuffle to his usual spot along the south wall midway between the front door and poker table. He diligently lays his tan tweed jacket over the back of his chair before using the table to steady his decent in a way that leaves his stiff left leg extended.

“Surprised you’re out given el commandante’s orders.” Armando offers.

“Don’t need no nanny telling me how to live my life.” The old man scolds. He’s trained Armando to bring a tap beer alongside a shot of rye, however, tonight being Cinco de Mayo, Armando decides to challenge the status quo. “I’m thinking tonight, in honor of Cinco de Mayo, we get you into something that is, shall we say, holiday appropriate. Might I recommend the casa Corona; a fresh but playful cerveza built and bottled by our beloved neighbors to the South. And to round out your celebration, I’m featuring a truly magnificent bourbon accompaniment. It’s a southwest delicacy made from organic blue corn grown along the Rio and distilled by that lawless desperado over there.”

The old man sizes Jake up. “I’ll stick with the tap but bring me his bourbon.”

Happy to have altered history, Armando prepares the beer and bump. He doesn’t collect money on delivery knowing the old man will pay with two fives plus two ones for a tip. It’s a routine that repeats itself with nightly consistency. The ANA watch the old man with interest because it’s odd he never brings anything to read, doesn’t watch sports on the television behind the bar, or immerse himself in electronics. Instead, he draws in this tattered black leather sketchbook pulled from his satchel. No one knows what the old man sketches, because no one ever talks to him.

“Check this out,” Preston enthusiastically announces as he passes out beers. “I’m in Santa Fe today, at the Coffee Beanista on account of they’re defying la dictator’s décret, and I’m yakking it up with this Buddhist. Out of nowhere he challenges me to explain the difference between ‘nothing’ and ‘no thing’.”

“Whoa,” Theo is impressed.

“I know, right?”

“So, what did you say?”

“That he had to first tell me, if the mind’s eye is near- or far-sighted.”

“Score one for the home team,” Dominic approves.

“And. . .” Theo presses.

“We’re meeting tomorrow to present our findings. For my part, I haven’t a clue, each time I think I have something; it turns out I don’t.”

“Are you saying you have nothing?” Jon teases, “or no thing?”

“Touche,” Theo smirks.

“Damn thing’s screwed with me all day,” Preston confesses.

“We’ve clearly been riding the same elevator,” Jake comments in a sour tone. “Just to different destinations.”