Chapter Two from the R.M. Dolin novel, “What Is to Be Done.“

“Something’s up,” Jake grouses between demanding draws of cold high desert air. Leaning left, he vectors his gray vintage bike off the poorly paved road, ratchets back to a climbing gear, then stiffly rises from the saddle pushing hard into the callous ascent. “No freaking way I make that mistake again.”

Above the road on a mesa no one’s bothered to name, an elderly elk lucky to have survived winter eluding wolves and weather, tilts back his head permitting massively chipped and tattered antlers to penetrate the entangled mass of dead juniper and piñon branches. Nudging toward the rock wall ledge, he stares down the barren side wall as wind stealthily steals her last breath from the still dark dawn to usher the oddly anxious rider up the last leg of his journey.

Jake’s lost to many manic thoughts before the rear derailleur’s finished down-shifting. He attempts to put context around his yet to be defined uneasiness by considering the juxtaposition of today being May fifth, as he inescapably reconsiders the causal link between that bright May day thirty-one years ago when he first met Emelia, and that desperately divergent March morning when his life suddenly, without warning, went to shit. Summiting the driveway, Jake pushes past the flat gravel parking area coasting the last ten yards to the courtyard’s arched entryway, unlocking his right foot from the pedal before swinging his leg over the horizontal bar to seamlessly dismount. “It’s all connected,” he castigates in a vain hope vocalizing the problem renders it solvable. Leaning his bike against the tan stucco wall with well-practiced fluidity, he strides across the flagstone courtyard aggressively working off sweat-soaked riding gloves. “This is gonna screw with me all freaking day.”

Dismissing an uneasy sense with no causal pattern has consequences, that’s life’s brutal lesson. That’s why Jake arrives at the Al Azar an hour before poker officially starts. “I’m telling you Mandy,” he reiterates, “something’s up.”

Armando slides a freshly made cocktail along the ancient oak bar toward his only customer. “Because it’s May 5th, or because the stupid-ass governor screwed me out of my busiest night of the year?”

“Do the math, that’s all I’m saying.”

Armando frets with the formerly white bar towel carelessly flung over his shoulder reluctant to open the Pandora’s Box Jake’s poking. “What’s it been, Cabron, three months? You’re all spun up about some mysterious sense when we both know what’s what.” Armando rubs his favorite bar stain, allowing himself to forget its trapped under multiple layers of lacquer. “Sometimes mi amigo, explanations remain elusive. I don’t mean to keep harping about our dumb-shit governor and her lame-ass mandates, but who the hell is she to shut me down?”

“It’s not about what happened,” Jake fires back. “Serious shit’s brewing, I feel it.”

“More serious than all our other shit?”

“Clearly things can’t get worse, but yes, it’s bigger than everything we got cooking.”

“The problem with bureaucrats is they’re always good,” Armando doubles back. “Good when times are good, good and when things take a turn. Just look at all the bullshit surrounding this made-up pandemic. No matter the shit-storm us real folks have to tread, politicians always swim in sunshine.” He pauses ready to let things go but then rallies back. “They have no problem shutting down small businesses, but do they miss a paycheck? Hell no. Do they miss a payoff? I don’t think so. Do they give up vacation days? Highly unlikely. Do they have to worry for even a moment how they’ll take care of their families? Not a snowball’s chance in hell! I’d like to take those ignorant, arrogant, panic-stricken pendejos and toss them on the street with nothing so they can feel just a little of what life’s like in my arroyo. Just cake and crap, Cabron, that’s all they know, cake and crap.”

“That’s about to change.”

“Damn straight.”

“Ya know what,” Jake announces, “you’re a shitty bartender. I come in early to talk about my issues and all you do is complain about yours.”

“Pay your bar bill, Cabron, then you can tell me how things ought to be.”

“It’d be worth it for a crack at that.”

Armando walks to the far end of the bar. “Yeah, yeah, yeah, always with the insight.” He grabs a can of Coors Light from his cooler. “A real guasón you are. Cinco de Mayo, Cabron, just another day, que no?” Armando stops in front of his friend, suddenly serious. “The problem with you Anglos is you can’t hold your liquor. Can’t figure a way to walk back your drama. Somehow that always ends with me in trouble.”

“Way to make it all about you,” Jake scoffs, “again.” He lets his whiskey melodically settle his soul. “Black bottle bourbon?”

“If you’re gonna talk nonsense, Cabron, what else can it be?”

Jake twirls the edge of his glass on the bar’s darkened lacquerer, tracing out recursive condensation rings that look like the spirals Einstein used to explain how light bends around large bodies rendering the universe relative. “So what if I fixate on the past,” he mumbles. “A man’s got the right to live where he feels most alive.” Jake nimbly manipulates the glass with hands worn hard from years of tactile contact with life. Honest hands that seek the solace of rough work. Hands covered with scars cut over scars in tattoo patterns of bitter lessons easily forgotten and bold adventures that never can. Hands that stutter at the magnitude of creativity and destruction they have wrought. Cracked and leathery, calloused so deep time can’t expunge the stain of imprisoned memories. “Here’s the deal,” he whispers. “I’ll always escape to a world run by logic because I’m compelled to live in one ruled by irrational hysteria.”

“Eee Cabron,” Armando sings hoping sheer exuberance can steer the conversation elsewhere. “It’s the Santa Anas for sure. Every time the damn pollen finally settles, she whips it back up just to piss me off.”

Allergy season is May’s main event, it lingers longer on the Sangre de Cristo side of the valley, which is the defining reason Santa Feans are more laid back than their central valley neighbors in Española, or the intellectuals in the high-tech town of Los Alamos perched on the Jemez Mountains side. Imagine all of Santa Fe entranced in varying regiments of anti-allergy treatment melodically moving like zombies in perpetual sedation. Earth-firsters seek homeopathic solutions, while the affluent trust-funders are convinced a steady infusion of Jake’s gin, made from local juniper and herbs, is the required elixir. For the masses however, relief involves a constant cocktail of whatever over-the-counter and prescription drugs make breathing possible.

“You could always move,” Jake quips.

“Pretty sure el Commandante outlawed moving right before she banned fishing. Besides Cabron, after five hundred years my blood’s adobe red. But you, with your fancy PhD and weapons expertise, you don’t have to make Northern New Mexico your paradise.”

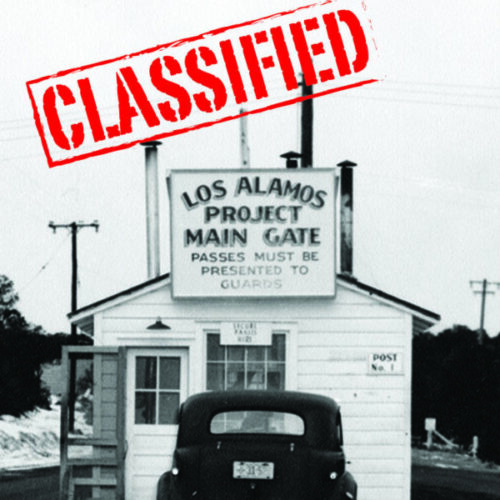

“Didn’t come for the allergies, that’s for sure.” Jake remains fixated on the cascading spirals convinced if he continues, he’ll finally get Einstein. “Keep in mind the Lab was a pretty prestigious gig back in the day. Just a grad school pup with potential, passionate to do my part to keep the country safe.”

“I started in high school,” Armando interjects. “We were only sophomores when Maria got pregnant, no one pays us locals like the Lab.”

“You should have gone to university?”

“What’s a hommie like me gonna do there?”

“Escape.”

“To what? My ancestors could have settled in Mexico, Colorado, hell even Texas if they wanted to forever disgrace the family. But they picked here. Why I can’t probably know, but who am I to question my elders? Besides, Cabron, the real world is fraught with expectations, so how does one enjoy life outside my land of mañana?”

“One summer,” Jake counter, “that was my commitment. But Decision Theory asked me to stay through a test shot. Figured what the hell, right; all-expense paid trip to Nevada.” Jake sips his bourbon allowing a lifetime of memories to flow along well trenched trails. “That was interesting,” he adds as an afterthought. “Then came Reagan’s Star Wars. I was for sure leaving when King George killed the Lab with his nuclear test ban treaty and the whole silliness of Stockpile Stewardship started. Fate felt otherwise though, and I was still on board when Clinton started selling secrets.”

“That was the coffin’s final nail,” Armando concurs. “No way China crawls out of their wagon wheel rice paddies without Clinton’s corruption.”

“When the Mind’s Eye project gets pulled,” Jake solemnly adds, “that was the end of the end for me.”

Armando’s mood suddenly darkens as he punitively wipes away Jake’s condensation rings. “That was some bat-shit kind of crazy you bastards got into.”

“Mea Culpa,” Jake mumbles with a repentance worn from repetition. Lifting his glass, he carefully examines the ratio of ice to liquid lamenting not being allowed to levitate like ice when drowning in darkness. “I wanted to leave, but Emelia had her chemistry gig and LA’s a great place to raise kids. I was done though, utterly empty.”

“Look at us now, Cabron,” Armando grabs his belly with both hands. “Fat pension, Cadillac health care, living large, wasn’t it worth it?”

“Not when you adjust the for the frustration of wasting talent on ridiculous crap to appease DC bureaucrats.”

“Life’s too short to not do something.” Armando sardonically counters.

“Exactly, I’d rather teach algebra to teenagers than deal with the mind-numb idiots in Washington.”

“Starting the distillery and winery was a stroke of genius,” Armando eagerly inserts.

“That was Emelia.” Jake’s mood softens as he flows over more difficult memories. “With her chemistry training and French heritage, the winery was a fait accompli. Unfortunately, there’s no engineering in wine. But distilling, mi amigo, each day’s sprinkled with sunshine.”

“You make the best bourbon for sure. And your gin, Cabron, muy bueno. Such a shame you don’t make Mula.”

Jake knows better than to take the bait. “We were a great team.” He lets the bourbon push against his hardest memory. “Each expansion, miscalculation, and mistake a memorable adventure. Which is why,” he strains to control the lump in his throat, “what happened was so hard.”

“The boys and me thought for sure you’d move back to North Dakota,” Armando jovially interjects in a desperate attempt to keep Jake from tripping down his rabbit hole.

“South Dakota,” Jake fires.

“Whatever,” Armando smirks. “It’s all kielbasa and lutefisk any way you fry it.”

“I do think about moving to a free state given the gulag we’ve become, but here’s the deal; while South Dakota will always be home, after thirty-five years of high desert living, I’ve become a New Mexican.”

“Talk to me when you’re here twenty generations,” Armando scoffs. “But, I suppose I’m glad you stayed. Poker wouldn’t be the same without your uplifting presence and the ANA wouldn’t even exist.”

Jake throws back the last of his bourbon. “Decisions do define us, even when we don’t get to decide.”

If you ask Jake or Armando to list the things they most enjoy, each will independently put playing poker every Thursday at the Al Azar in their top five. What’s odd though is today’s Saturday, and in all the calculus of Jake’s anxiety riddled analysis about ominous undertows, it never occurs to him that a compounding factor is Armando moving poker on account of Cinco de Mayo and his bar being closed by the pandemic police. It’s odd indeed that a person so perceptive in how the past provides a pretext for the present, doesn’t see so many catalysts converging. Perhaps though, it can be explained away by the extent to which his mind is lost to the madness of memories.