Chapter 20 in the R.M. Dolin novel, "What Is to Be Done"

Read companion poem

Einstein postulated that time is not constant, at least not in ways humans discern. According to Al, as we approach the speed of light, time slows down to a more manageable variable in the theoretical equations of life. Imagine the implications of being able to harness the power of time, for example, space travel to distant stars thousands of light years away would be possible. Taking Al’s hypothesis one step further, if time could be slowed, could it not be stopped? What would our lives be like if we stopped time long enough to figure stuff out; giving nations on the brink of war the opportunity to work through differences. By extension, if time could be stopped, how much harder would it be to reverse? Who among us would not rewind time to a more elusive moment? Imagine a universe where time was our diminutive minion.

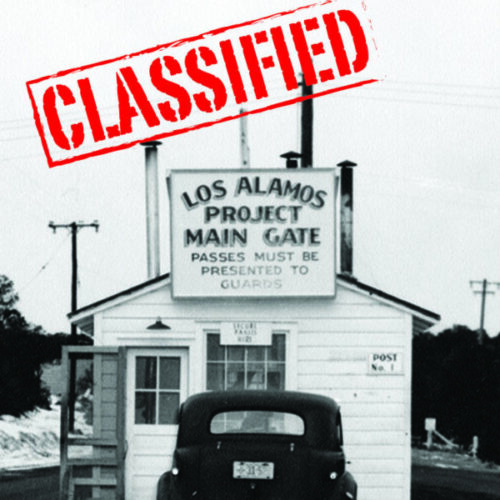

“Would be sweet,” Jake whispers to the pre-moon night as he settles into the canvas camping chair positioned in the entryway of his spirits barrel-aging room facing east toward the Sangres that rise like a formidable fortress over his property in a majestic mix of mystic wonder and impenetrable power. In May, the snow-covered peaks seem to hold up heaven itself while remaining close enough to touch. Across the valley the sanguine sun long ago escaped behind Pajarito Mountain. At ten thousand four-hundred and forty-feet, Pajarito’s not the tallest peak in the Jemez, but close. The east slope of Pajarito is home to the Los Alamos National Laboratory, where during World War II, the super-secret Manhattan Project built the world’s first atomic bomb in the shadow of what is now Pajarito Ski Area. Engineers still visit the very room where the two atomic bombs dropped on Japan were assembled. They can’t linger though, as the ever-persistent radiation continues to scoff at man-made protection. No matter how many times Jake’s visited, he always leaves with a solemn heaviness, as if the gravity of fifty-thousand souls were squeezing him past the point of remorse. From its prestigious perch today, Los Alamos looks out over the entire upper Rio Grande valley like an awkward cousin unsure of their place in a tightly integrated family.

The back side of Pajarito drains into the Valles Caldera’s twelve-mile-wide volcanic crater. Today the Caldera is a high mountain meadow with herds of wild elk and domestic cattle grazing side by side on lush, calcium rich, buffalo grass. Sixty-thousand years ago though, this was a much different place; that’s when the last in a series of eruptions spewed the Caldera’s molten lava down Pajarito onto the valley floor. The highest point along the caldera’s rim is Redondo peak clocking in at eleven thousand two-hundred and fifty-eight feet. Geologists estimate the volcano’s first, and probably largest eruption, occurred 1.25 million years ago. Prior to that, Pajarito, which at the time encased Redondo Peak and the entire Caldera, easily surpassed Mount Everest as the world’s tallest mountain. That first eruption occurred with such kinetic intensity, twenty-ton boulders from the obliterated peak blasted all the way to Oklahoma.

The Valles Caldera remains the largest of the world’s six known land-based super-volcanoes and is remarkably, still geologically active. This accounts for the many hot springs and natural mineral baths dotting the Jemez Mountains. Ironic barely begins to describe how the world’s foremost research Laboratory and premiere plutonium manufacturing facility, came to be located on the world’s largest active volcano. It more than proves the point about government intelligence being an oxymoron.

The southern slope of Pajarito drains into Bandelier National Monument, famous for its ancient Anasazi ruins. Predating most known civilizations, the Anasazi possessed technology like calendars and complex irrigation. As gifted horticulturists, they’re responsible for blue corn, which served as a staple for thousands of years throughout the American Southwest. Blue corn eventually mutated into the more widely pervasive white and yellow varietals as it migrated north and east and today corn is so ubiquitous its journey from simple Anasazi beginnings is overlooked. Evidence suggests that the Anasazi’s knowledge of healing was so extensive it still has not be matched by Western medicene. Their language and appreciation of art demonstrates a level of learning that many scholars say even today has not been equaled.

While all of this is interesting, what make the Anasazi fascinating is that five thousand years ago, at the height of their civilization, they vanished. One year they’re thriving in Northern New Mexico and the next, gone. Not gone in a migrated south to Mexico way, but in a left the planet way. No evidence of what happened has ever been found. There are no indications they were wiped out by disease, or met a violent end at the hand of marauders. They didn’t resurface in another local or assimilate into another culture. They simply vanished, leaving behind intricately excavated lava dwellings and a smattering of artifacts.

What captivates academics, is that no other civilization in the history of the world has ever disappeared without leaving clues to unravel their mystery. Many theories postulate what might have happened, from the logically obvious, to the sublimely ridiculous. The theory most plausible to Jake, is that the Anasazi simply finished what they came here for and went home. Of course to accept that, one has to accept that earth was once inhabited by extraterrestrials; something Jake’s got no problem getting behind.

Stepping into the large parking lot from spirits barrel room, Jake relights his cigar while somehow managing to hold both the lighter and bourbon glass in one hand. He gazes deep into the still moonless sky contemplating the implications of time travel. Thoughts take him beyond what can be held, touched, or known with certainty as he marvels at the Sangre’s wind-swept peaks rising above his house like giant space aliens.

Jake explains Einstein’s theory of time travel by relating a trip he took to Japan when invited to lecture at the University of Tokyo. On his return, he departed at six in the evening and after an eleven-hour flight, arrives in Portland at five that same evening; in other words, arriving one hour before taking off. However, because he did not travel at light speed, when he touched down, he was eleven hours older despite what the clock indicated. The added benefit of traveling at light speed, according to Al, is you don’t age in transit. Since most stars are more than five thousand light years away, the Anasazi could still be traveling home, the same age now as when they left New Mexico.

Jake sets his cigar in the chair’s ashtray and saunters into the barrel room where he takes a moment to appreciate the two-hundred vessels of bourbon, rye whiskey, and brandy he and Emelia put up. The brandy barrels are neatly stacked four high along the south wall with their pristine heads proudly promoting each French cooperage that crafted the barrel. Bourbon and rye barrels line the other three walls, their warped barrel heads are branded with Jake’s company logo and a collage of black stains from whiskey mold.

Jake ages bourbon in Missouri oak barrels, and while there’s no regulation regarding Rye whiskey aging, he uses Missouri oak as well. One feature of American whiskey barrels is they leak. To mask their lack of quality, American Coopers invented the term ‘Angel’s Share,’ as a way of quantifying the portion of a barrel’s contents lost to leakage. Jake’s found that in the hot dry New Mexico climate, Angels claim about five percent of a barrel’s volume per year. While it sucks losing volume, American barrels only costs one-hundred and fifty dollars, whereas an equivalent French brandy barrel, with higher grade materials and craftsmanship, costs fifteen-hundred dollars. Per federal regulations, bourbon barrels can only be used once, while brandy barrels can be reused indefinitely. With a tighter seal and ability for reuse, the more expensive French barrels actually have a lower life-cycle cost.

Better quality French barrels is why brandy contributes little to the room’s aroma. Conversely, the angel’s share from his leaky whiskey barrels lights up the room with aroma. It’s why on nights like this Jake sets up in front of the spirits room, while nosing a glass of bourbon takes him through the journey that spirit took from raw grain to bottle, standing in the barrel room immerses him in a symphony of memories emanating from over a hundred barrels. The conjuring of emotions is like a maestro’s mesmerizing music where each barrel contributes a unique texture. On good nights, Jake’s able to summon memories and emotions all the way back to the first barrel of blue corn he and Emelia put up; a barrel he still holds in inventory but rarely opens.

Stepping into the spirits room is equivalent to stepping back in time, each barrel possessing treasured memories, each rack of barrels capturing ensemble moments. Depending on where Jake stands, different memories are conjured. His sacred spot is the back corner where the oldest barrels live, where his most treasured blue bottle barrels rest. Jake’s barrel management philosophy is to completely drain a barrel once unsealed. His blue bottle barrels are the exception; these barrels are siphoned off one bottle at a time. He does not dilute this bourbon with water to achieve a desired proof, nor does he filter; too much of the magic that time, nature, and kismet instilled in the spirit is lost during bottling.

“Everything I own,” Jake tells his angel, “even my life, matters less than our blue bottle bourbon.” He closes his eyes allowing tonight’s aromas to loft him over happier times. “No doubt you’ve noticed I’m dealing with some pretty surreal stuff.”

The danger with time travel that even Einstein never mitigated, is controlling how far back you go and where you end up. In the spirits aging room, time and place are determined by bourbon barrels and how his Angel takes her share. For all the difficulties Einstein had perfecting time travel, it’s a relatively routine undertaking for Jake. Most nights he soaks in the gestalt of aromas, but when focused on individual barrels he’s taken to exact moments in time. His blue bottle barrels usually transport him to happy moments, but regrettably, sometimes they steer him to the night of his ill-fated drive to Santa Fe, and the terribly dark days that followed. Jake’s learned that when feeling deep and reflective the aroma of blue bottle bourbon teleports him directly to the night his angel began her good-bye. He recognized while setting up outside, this was one of those nights so, rather than risk the back corner, he opts for the center of the room allowing the symphony of aromas to serenade softer memories. Most nights that’s sufficient; tonight though, probably on account of what the May moon means, it’s more of a struggle.

The barrel room is a framed stucco structure sandwiched between the distillery and wine barrel room. It has a large ten-foot by ten-foot door permitting tall or wide loads to move in and out with a forklift. The view from the doorway to the majestic Sangre’s is fantastic. Moonrise over the Sangre’s is far more spectacular than sunrise due in part to the fact you can watch a moon rise. At certain times in the lunar calendar, the full moon crests the Sangre’s as a massive blood orange ball illuminating the dark New Mexico sky in an unmatched cosmic show of color and intensity. Tonight’s moonrise is extra special because it occurs in the saddle between Santa Fe Baldy and Truches Peak, the two tallest mountains in the Sangres. Watching the event is a much-anticipated tradition he and Emelia began even before they bought the place. “Tonight’s our anniversary moon,” he reminds his angel.

Sympatico was invited but given how things are between them, she probably won’t come. They talked about the incident in the courtyard, and she understands there was no intent, but Jake’s not convinced she forgives him. Even though Quando continues casting condemnation, Jake hopes he at least comes out, they have a full moon ritual that’s highly cathartic and tonight Jake feels an acute need for canine remediation. In solemn reverence Jake lifts his bourbon glass toward the Sangre’s, “here’s looking at you kid.”

As an orange glow begins to back-light spruce trees lining the saddle’s edge, Jake settling into his camping chair and re-lights his cigar sensing time travel’s emanate. On nights when the still quiet of deep dark sky couples with bourbon vapors dancing around his barrels, Jake’s transported to the first time he and Emelia watched the full moon rise over this very spot.

#

“The Realtor called,” Jake offhandedly offers after promising himself not to mention it. “A new place just opened.”

“We agreed on the Valdez house.” Emelia dismissively counters while collecting leftovers and discarded dishes.

“Can’t hurt to look.”

Emelia knows as soon as they look Jake will start agonizing. The flip side though is if he doesn’t look, just the possibility of a better property being out there will fester like slow growing bacterium. The only way to vanquish his uncertainties is to see the property so it can be summarily rejected as were all the others.

As their car bounces over Otowi Bridge, Emelia looks out the window recounting a lifetime of challenges and adventures that ebb and flow like the Rio itself. Crossing Otowi always symbolizes the end of a journey or the start of something interesting, depending on if you’re moving uphill to Los Alamos or down to Santa Fe. “Just imagine,” she states in well-traveled pangs of remorse, “in five weeks our life in LA is really over. Papa would be so proud, though, I’m starting a winery.”

“The place won’t amount to anything,” Jake dryly says.

From the strain in his voice, Emelia knows the agonizing’s begun. A car, computer, tires for his bike; Jake only makes decisions after painful deliberation and a life-altering decision like this is his perfect storm. The prospect of moving is unsettling enough, but retiring only to start a winery is fraught with pressure and commitments that are flat out consuming. Emelia grew up making wine beside her father in France and developed an even deeper understanding as a chemist. Jake doesn’t know anything about wineries; and that’s about as uncomfortable as things get for him. Now there’s this whole new property parameter chewing up his chaos. “Oh, stop it,” Emelia teases, “you don’t like change, I know. But show some moxie, this is after all our second grand adventure.”

“And the first was. . .”

“Getting married silly.” Emelia places her hand on Jake’s knee. “I don’t know about you, Louie, but our friendship’s been a pretty wild ride.”

Jake smiles at his beautiful bride. “Wouldn’t trade a day.”

“This place can’t possibly be better than the Valdez house. No way it has cottonwoods as spectacular and its not along a river.”

“Cottonwoods got a gazillion leaves, and the Nambe’s not really a river,” Jake counters.

“Stop that, you like it more than me. Walking distance to the Al Azar, you keep saying.”

“So why bother looking at this place?”

“If we don’t, I’ll never hear the end of it. You’re the one always saying, that without opening the door, you can’t know what’s on the other side.” She pats his knee. “You’re as predictable as rain in July, Louie; it’s your most endearing trait.”

It’s just before sunset when they summit the steep pumice driveway leading to the hacienda style house atop the modest mesa. The house is surrounded by a suffocating circle of juniper trees with narly trunks and wildly interwoven branches that prevent penetration. It’s as if they tried standing alone, but years of harsh winters, high winds, and blistering heat compelled them to join forces for survival leaving them shadowy remnants of their once inspiring potential. The path from the small parking area to the house is through a saltillo-tiled courtyard. What was once a large garden fills the flat space between the back of the house and forest. Emeila asks if there might be drip irrigation, already planning her small vineyard.

Directly across the parking area overgrown by juniper, sage, and chamisa, stands an old barn with badly weathered siding. It’s big doors barely hang on rusty hinges and the dirt floor is unevenly pitted. Windows lining both sides are scattered with broken panes that oddly complement the weathered corrugated roof with open areas. As Jake makes mental notes of each of the property’s failings, Emeila’s bustling winery is taking form; she already sees the old barn filled with magnificent French barrels containing New Mexico’s finest vintages.

The anxious Realtor hurriedly highlights as much as he can before night shadows creep down the Sangrias. Emelia though, stubbornly takes her time. “The house is decidedly nicer,” she concedes as the Realtor leaves. “I do wish the courtyard was flagstone though.”

“No cottonwoods,” Jake grouses, glad he no longer has to filter his words. “We’ll bake without shade.”

“Better views,” Emelia counters. “Just look at Pajarito and how it frames the barn in sunset like an Ansel Adams calendar.” She walks Jake to the center of the open space between the house and barn. “And the Sangre’s, even you have to marvel at the way they rise like lumbering giants behind the house.”

“That driveway’s insane,” Jake argues, “long, steep, and dusty. Imagine going up or down that after a rain?”

“Seriously, Louie, we’re in a desert.”

Jake grins. “You got something for everything don’t you?”

“Oh, Louie, you see through all my charms.”

Jake and Emelia linger long after the Realtor’s left weighing the pros and cons of this property versus the Valdez house. As darkness deepens, they meander hand-in-hand toward the old barn, stopping where the spirit barrel room now stands. It’s at that moment the bold blood orange May moon majestically lofts into the saddle between Santa Fe Baldy and Tres Padres like an eager child peeking over the upstairs banister on Christmas Eve. This iridescent interloper awakens the property with an alien-like awe casting both the mood and moment in a surreal veil of hope and promise. Emelia stares in amazement as the engorged moon spills orange light down the Mountain’s watershed straight into her soul. As if metaphorically physical, the moon docks in the saddle between peaks like a performer taking center stage. “Of all the gin joints in all the world,” she says in stunned awe reaching out expecting to touch the moon’s intensity. “This is home,” she whispers with moonstruck wonder.

Emelia takes Jake’s hands smiling playfully, knowing from a lifetime of agonizing he’s not ready to surrender his Nambe dream. “Here’s the deal, Louie, if you say yes-,” She runs her hand behind Jake’s head and along the nape of his neck. When she reaches his chest, she looks provocatively into his eyes while unbuttoning the top two buttons on his shirt. “I’ll make it worth your while.”

“Look Ilsa, don’t go thinking you can manipulate me so easily.” Jake attempts to be stern, but his voice already betrays weakness. He long ago learned in all matters related to his bride’s determination, resistance is futile.

“Oh Louie.” She continues letting the next two buttons loose. “You have no idea the measures I’m prepared to deploy.”

“Here!” Jake exclaims in modesty-laced horror while looking around the dark empty parking lot. He’s many things, but an exhibitionist he’s not.

“Not only now,” Emelia whispers in his ear as the last button constraining his restraint finds freedom. She runs her soft hands around his waist and nibbles on his neck before whispering into his hyper-sensitive ear. “Every May moonrise for the rest of your life will have an equally happy ending.”