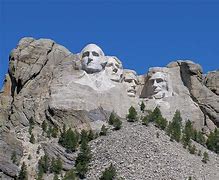

I spent today thinking about President Trump holding a fourth of July ceremony at Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills of South Dakota. I wish I were there, not to support Mr. Trump; he’s doing just fine without me. Rather, in this time of medical crisis, social crisis, economic crisis, and constitutional crisis, I feel a compelling need to stand shoulder to shoulder with my fellow Americans and honor the four presidents who have meant so much to our Nation while listening to our current President explain his plan for bringing the nation back from the brink.

I grew up in the shadow of Mount Rushmore, living six years in Spearfish, two years in Sturgis and four years in Rapid City. And while my home is now in New Mexico, I still go back at least twice a year and I never get tired of that short drive up to Keystone and then over to the monument. Never is the journey not filled with a moment of awe and a profound sense of pride upon the first glimpse of the giant granite carved mountain, not only from the marvel of what Gustav Borglum and he crew accomplished, but for what the monument means.

When I was in college back in the 1980’s, I often snuck up to the base of the monument, over where the pile of granite tailings left over from the blasting and carving still rest. I liked to just sit there, sometimes at night, putting my life in perspective; alone in a peaceful place where I would be arrested if discovered. Not only was I a naïve engineering student who had no legitimate right to be at a school ranked in country’s top forty, I was in way over my head and floundering.

Because I didn’t take high school seriously and graduated seventh from the bottom of my class, I was not prepared for college. Like most kids in my rural South Dakota high school, college was not really on my radar. I had worked as a plumber since I was fourteen, and only attended high school to make my Mom happy. At eighteen my future was solidly set in the construction trades, first as an apprentice, then a journeyman, and then running my own shop someday.

At nineteen, after a hard year on the road working commercial construction in places like Worland, Wyoming, Ashley, North Dakota, and Brainard, Minnesota, I started to see the world and my place in it a bit differently. My new goal was to get an engineering degree so I could fly fighter jets off aircraft carriers. Of course it’s an outlandish goal for a small town kid who graduated at the bottom of his high school class, but America has always been a place where any dream can come true if you work hard enough and never give up. If anything defines the American spirit that’s at such jeopardy of being lost, it’s that everyone and anyone has the opportunity to get where they want to go if they’re willing to walk any road and endure any hardship.

Sitting at the base of Mount Rushmore as an out of sorts freshman who didn’t understand basic algebra and wasn’t really even sure what an engineer was, I took solace in the fact that the men whose faces loomed above me in the moonlight, probably had similar doubts at certain points in their lives. Unsure if I could survive the next exam, the next semester, or the next year, I drew strength from the way each of those men were tested in ways few ever would and how they somehow managed to endure. I turned that lesson inward and ten years later was a Ph.D. leading research teams at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, the most prestigious intellectual institute in the world.

I never got to fly fighter jets off carriers, but the great thing about America is that dreams are allowed to change and I found other ways to serve. In addition to a thirty-five year career in national security and homeland security, I served on the U.S. Senate Border Security Task Force, the Department of Justice (DoJ) Anti-Terrorism Task Force, the DoJ Human Trafficking Task Force, the New Mexico Homeland Security Task Force, the POTUS/DHS Pandemic Flu Task Force, and the U.S. Secret Service POTUS State of Union security detail.

As President Trump stands in the shadow of Mount Rushmore being challenged in ways he never has before, I hope he can draw solace and strength from the larger than life statue before him. And even more important, I hope we all can appreciate that in times of crisis Americans are first and foremost, united as one soul struggling to endure and persevere toward a better tomorrow. And I challenge anyone who can honestly say they don’t want to see our President succeed, who don’t want to see our country succeed, to meet me at the base of Mount Rushmore, just to the east of the great granite pile Gustav Borglum left behind, there we can discuss why it is you want to be an American at all.