For other COVID posts, visit my Quarantine blog.

For the past couple months I’ve used numerous approaches to ascertain the extent to which CDC data may be skewed. I used data from past pandemics, from previous flu seasons, and from other health catastrophes. I highlighted instances of the CDC overruling medical assessments to count nonCOVID deaths as COVID related. I pointed out the financial incentives behind hospitals and doctors inflating COVID counts. Overall, the preponderance of evidence tilts toward the CDC over-reporting COVID deaths.

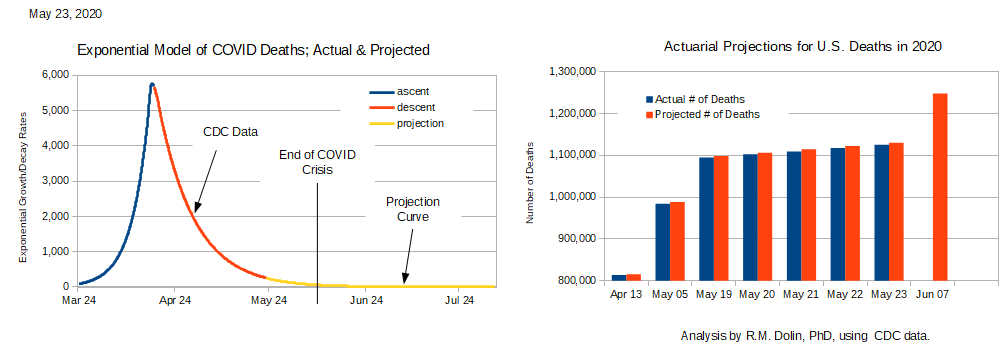

Most recently I’ve been using actuarial data to estimate the number of Americans that were going to die from something this year (red bars in the above chart). Notice how closely those projections track with the number of deaths that have actually occurred (blue bars). The actuarial predictions are based on pre-COVID inference, which means that once the COVID crisis is factored in, the actual number of deaths should exceed projections; only they don’t.

To date, 4,635 fewer Americans have died this year than were projected to die. Several of you have suggested logical reasons why in the midst of this pandemic the aggregate number of deaths are lower than expected. These include

- Lockdowns have lowered accident rates. In the sanctuary of our homes, we drive less, don’t go boating, no hang-gliding, etc.

- Hospitals delaying elective surgeries drives down doctor caused deaths. According to Scientific America, 440,000 Americans who go to hospitals for care each year die from preventable causes.

- Social distancing has lowered the number of flu deaths, which typically range from 30,000 to 60,000 annually. According to the CDC, no one has died from flu this year, as the CDC counts all respiratory deaths as COVID caused.

- Crime is down, as are violent crime deaths.

- The homeless death rate is down. Many cities put their homeless population in hotels and other shelters when the crisis began.

- Noncitizens are returning to their home countries, which means our population is decreasing.

- Conversely,

- Suicide rates are higher this year.

- Incidents of obesity, diabetes, heart aliments and other health related issues are increasing, which represent delayed deaths.

- Child immunizations are significantly down – delayed deaths.

- Drug overuse is increasing, both legal and illegal use.

For these reasons we cannot assert that the delta between projected deaths and actual deaths represents people who died due to the coronavirus. However, we can apply CDC logic to assert COVID caused some death rates to increase, like suicide, while causing other death rates to decline, like doctor caused deaths, even though neither death rates were impacted by the coronavirus itself. In the aggregate, CDC logic allows us to assert that due to COVID, fewer Americans are dying this year than were projected to die. We can further assert that lockdowns saved 4,635 lives, although we still can’t conclude how many of the 1.1 million Americans who have died so far this year died from the coronavirus.

I ‘m not a fan of CDC logic because it’s fallaciously irrational. For example, suppose the 440,000 doctor caused deaths are prevented by stopping all elective surgeries, which is what happened during lockdown, what then happens to the millions of people who are not treated? Similarly, if we stop driving we eliminate vehicle deaths, but then how do we get around? Don’t say public transportation because buses, trains, and aircraft all experience accidents.

The White House has finally started questioning the logic behind how the CDC attributes deaths to COVID, suggesting the actual numbers are lower. The CDC has so muddled the data pool with inconsistent and felonious counting it is not possible to extract a reasonably accurate estimate of the number of Americans who have died from COVID illnesses. All we are left with is an aggregate accounting of the number of Americans expected to die this year relative to the number who actually die. On that account, we’re having a phenomenally good year because even in the midst of a global pandemic our death count is 4,635 below expectation.

Conclusion: It’s not possible to eliminate death and none of us are making it out of this world alive. While we all want to be safe, it’s not reasonable to diminish quality of life in the name of reducing deaths below some arbitrary threshold. Governors in lockdown states diverge from governors in free states regarding what’s a reasonable infringement on our quality of life in the name of achieving their desired threshold. While a prairie state governor may advocate for improving safety by eliminating snow skiing, that probably won’t sell well in mountain states. Desert state governors might propose closing lakes as a way to reduce accidental deaths, while states rich with sport fishing and water recreation might object. East-coasters may be okay eliminating cars, but people out west can’t survive without them.

Looking at this issue in the small leads to a different perspective than looking at it in the large. In the small, getting a haircut may not be worth risking COVID caused death. However, in the large, being able to support my family and live my life is worth the risk; in part because I have decided it’s acceptably small. It’s the same risk versus reward analysis I perform each time I fire up my truck or sit down on a chairlift.

In the pursuit of minimizing COVID deaths there are unintended consequences, like increased suicides. Likewise, few people advocate that driving or elective surgeries be outlawed even though that would save far more lives than COVID has taken. For many of us, the sage philosopher, Jimmy Buffet, captured our sentiment best when he said, “I’d rather die while I’m living, then live while I’m dead.”