Charcuterie is a broad term used to define turning fresh meat into meat that can be preserved in a process called curing. If you’re lucky enough to live somewhere where you still have neighborhood deli’s making sausage, the butcher would be a Charcuterie. For centuries, charcuterie was an art form and butchers were known for their specialty sausages just as chefs today are known for their cuisine.

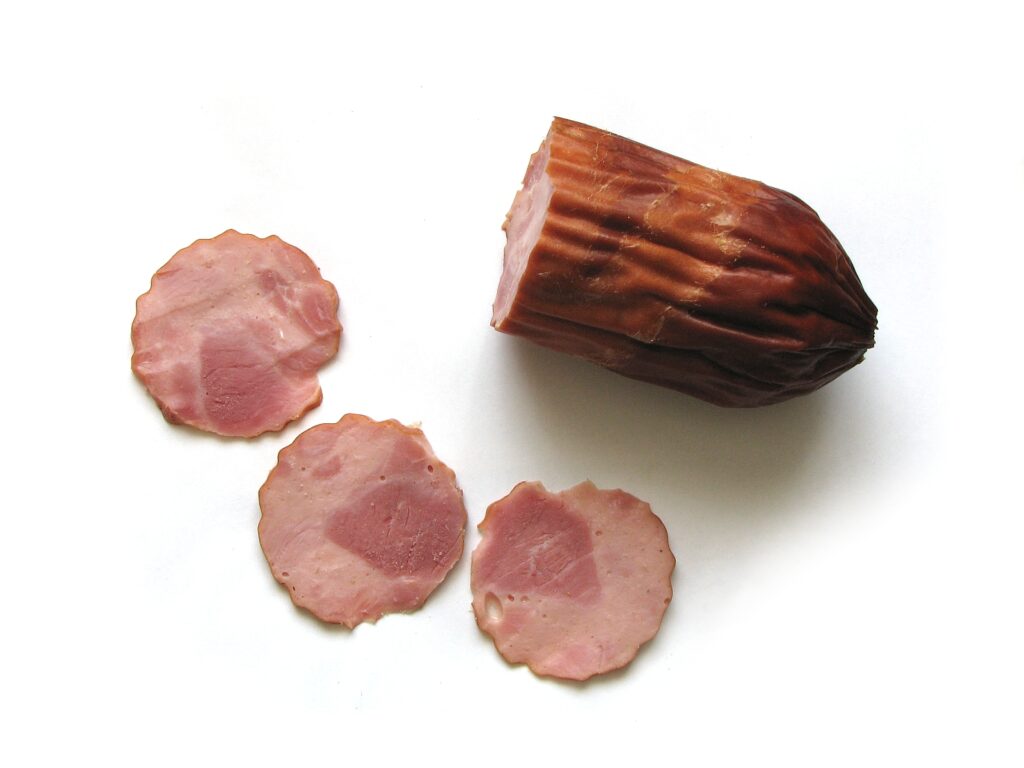

When I was working on my PhD at Purdue University, I would fly through Chicago when going and returning from West Lafayette. I always planned my itinerary for a long layover at O’hare, for two reasons; one was to buy handmade Perogies from the ladies at the nearby Ukrainian Orthodox church, and the other was to visit a Polish deli on Chicago’s North Harlem Avenue that made the best Krakowska. The only problem was that no matter how carefully I wrapped the Krakowska, my overhead compartment always reeked of garlic by time we landed.

On one trip between Chicago and Albuquerque, I was carrying two kilos of Krakowska and wasn’t paying attention when the cabin steward helped an elderly woman put her expensive fur coat in the overhead beside my backpack. When we landed and opened the overhead, the plane filled with the smell of garlic and passengers were less than hesitant to express disapproval. As I profusely apologized to the elderly woman while tentatively handing her the expensive garlic infused fur coat, she gave my arm a tender squeeze, smiled fondly, and said in a thick Polish accent, “it reminds me of Krakow as a small girl.” These days I have to drive all the way to Denver to find the fine art of charcuterie still being practiced, and the best places there are the Russian delis. If you’re ever in Denver, I recommend the M&I International Market to get your homemade salami and gourmet dessert fixes.

It seems every culture in the world has some form of cured meat. In Polish culture, Kielbasa is the term for any kind of meat sausage, cured or uncured. In America, Kielbasa has become somewhat bastardized for a commercially produced, poorly prepared sausage that large packing houses put on grocery store shelves in the name of delicatessen. The Irish have corned beef, the Italians have salami (Genoa, Felino, Sopressata, Pepperoni, etc.), and Latin cultures have Chorizo. Asian culture is rich with cured pork bellies (i.e., bacon), African cultures have Biltong, and Middle Eastern cultures have Basterma. These examples are just scratching the surface of international charcuterie cuisine, and we haven’t even mentioned fish. I just made a salt-cured, cold-smoked salmon for Christmas, and Gravlox is one of my kid’s most requested dishes, which they like to have on top of a cream cheese bagel.

Most coastal cultures have some form for cured fish, for example, I had an incredible cold smoked herring once in Sweden when an amazingly beautiful Polish Post Doc I met in Los Alamos, who’s family had escaped communist controlled Poland when she was a little girl, invited me to visit her in Stockholm and Gevalia. We had just come out from watching the midnight showing of Knotting Hill, and since it was still as bright as day because we were above the arctic circle, we went for a walk along the beach and stopped at a cafe for beer and herring. Two essential parts of enjoying food is how you enjoy it, and who you enjoy it with. Sometimes I wonder if the cold smoked herring really tasted as good as I remember, or if the whole experience is what’s captured such a prominent place in my memory……

Ah but that’s a post for another time, our focus here is on the meat curing process, where the science is basically the same whether you are making a country ham, bacon, snack sticks, fermented salami, or cold smoked fish. The biggest distinction between all the various cured meats, beside the meats, is the processes that different countries and cultures have developed. At the highest level, there are two broad meat curing processes; slow-cured and fast-cured. Within these two processes are where each different type of cured meat develops their special character. Fast-cured meats are cooked, or hot cured, are ready in a day, but must be refrigerated and have a limited shelf life. Slow-cured meats, also referred to as cold cured, are fermented in a carefully control environment, can be stored for long periods without refrigeration, but take months to fully cure.

Most DIY Charcuteries already have the basic equipment to hot cure meat in some form in their kitchen, but some hot curing techniques do require specialized equipment. Cold curing requires a carefully controlled environment during fermentation and/or aging, which needs special equipment to manage temperature and humidity. Cold curing meats usually involves cold smoking, which is another technique requiring special equipment. Part of what makes DIY Charcuterie interesting is engineering workarounds to expensive equipment with things you find at thrift stores or garage sales. In a previous post, we discussed the general equipment needed to hot cure meat and showed how you can get started for as little as $22 in equipment costs.

Curing Recipes

There are many differences between cured meat recipes, for example, some are based on an uncased final product, like bacon, corned-beef, or country ham, while others will be cured in casings, like kielbasa or salami. Cased meats can have either edible casings, like in sticks, or non-edible porous, peel-off, casings typically used in salami. Different recipes will vary greatly in spices, but the spices themselves are not part of the curing process, with the exception of salt, which is the primary curing agent. There a two distinct kinds of salt in meat curing recipes, normal salt, which is sodium-based, and curing salt, which is sodium nitrate based. Salt is so essential to the curing process, that we need to spend some time discussing it.

Regular table salt is mostly sodium, while curing salt is a blend of sodium and sodium nitrate, along with other preservatives. When using a recipe that calls for table salt, you want to use a salt that does not contain iodine, like Kosher salt. Most table salts have iodine added, I could do an entire blog on why, but it has to do with a cholera outbreak in London in 1853 when John Snow discovered cholera was water borne and could be prevented with an increased intake of iodine, so they started adding it salt. Today, if anything, people get too much iodine in their diets but doing away with iodine no one really needs would be like asking a liberal to stop wearing their Fauci face-mask. Also, stay away from the Yuppie salts like Himalayan, because they have a lower sodium content and higher mineral content, which is great for easing the collective conscience of the health food crowd, but comes up short on it’s duties as a curing agent.

Salt has been used for thousands of years to preserve food and allow food to be stored for longer periods. The Romans, who elevated meat curing to an art, could more effectively move their armies around because they relied less on fresh meat for protein. Regular salt is good for drying meat, but cannot kill the harmful bacteria that causes meat spoilage and illness, which is the main reason smoking food got to be a thing. Smoking meat provides an added preservative that helps address the harmful bacteria issue, although it does not completely remove the need for curing salts.

There are two types of curing salts, cleverly labeled curing salt #1, and . . . wait for it . . . curing salt #2. These two salts are also called Prague salt or pink salt and cannot be substituted for one another and, again important, cannot be used as a substitute for table salt. Curing salt #1 is used for hot cured meats while curing salt #2 is used for cold cured meats. These are two very different salts, so again, be careful to use the correct salt for your curing process.

Salt is the workhorse (pardon the pun) of the meat curing process. Salt removes moisture from meat and in doing so, dehydrates bacteria. However, salt alone cannot kill bacteria that can, for instance, cause mold or a rancid taste. The clostridium botulinum bacteria that causes botulism is not killed by standard salt and can even survive at high temperatures after cooking once it gets going in the meat. Meat can be cured without using curing salts, but it requires special techniques, such as those used when making country ham or cold smoked fish. However, the sodium nitrates in curing salt kill the botulinum bacteria and are used extensively in commercial cured meats, like the salamis you buy at the store.

While you need to use the right curing salt in the meat you’re processing, you only use a small amount and you want to be careful not to use more than required. For this reason, you need to follow the curing salt manufacture’s guidance. I use Anthony’s curing salts in my recipes, so keep that in mind if you use a different brand because the amount of curing salt you should use in a recipe can vary from what I might specify in my recipes. Curing salts are typically dyed pink to not confuse them with table salt, that is until Himalayan salt became a thing.

Some health food experts worry about how the body reacts to the sodium nitrates contained in curing salt, but they are ubiquitous in the package foods you blindly consume, unless you are like me and avoid processed foods. Even fresh produce contains nitrates, with spinach and celery containing ten times more nitrates than cured meats. Nitrates do a lot more than prevent botulism, they help the meat develop a rich color during curing. Without nitrates, the meat would turn grey, like cooked meat. This is because the meat’s myoglobin, which stores oxygen, gets depleted during the curing process. Nitrates are also a meat preservative and keep mold and other bacteria from gaining a toehold.

After the meat is prepared, you must complete the curing process by one of three methods: 1) cooking the meat (hot cure), 2) aging the meat in a carefully controlled environment (cold curing), or 3) cold-smoking.

HOT CURING: This simplest way is to complete the hot-cured process is to cook the meat in the oven, first at a low temperature, like 130 F. for 3 hours and then raising the oven to 170 and turning off. The important thing in hot curing meat is to make sure your meat gets to the right temperature, generally 165 deg. F. We will discuss many ways to accomplish this in subsequent posts. Hot cured meats must be refrigerated and have a limited shelf life.

COLD CURING: Cold cured meats can be fermented in a temperature and humidity controlled environment, like salami, or air dried in a less controlled environment, like a traditional Kentucky country ham or Spanish Jamón. Salami takes three months to cure, while air-dried meats can take up to 12 months to fully cure. Cold cured meats do not have to be refrigerated and have an extensive shelf life.

COLD SMOKING: This technique is mostly used to cure fish, although cold smoking is also used to flavor cheese, and help both flavor and preserve cold cured meats. Turning fresh fish, such as salmon on herring, into a smoked delicacy is a three day process that only involves table salt and sugar for the initial curing stage and cold smoking to complete preservation. Cold smoked fish has to be refrigerated, but has a long shelf life. The important thing when cold smoking fish, particularly salmon, is to not cheap out with farm raised fish, pay a bit more for the wild caught fish. Yes it costs more, but doesn’t everything worthwhile in life? I recently purchased wild caught salmon fillets for $12/pound. It cost me less than $1 in salt, sugar, and wood chips to cure three pounds of fillets. Three days later, I had a smoked salmon better than the dried up stuff they sell for $3/oz ($48/lb) at the yuppie health food stores.

I’ve spent time with solid fishermen in Eastern Europe who salt their freshly caught fish and then hang it in the sun to air dry. While this is a century’s old process, I find the result too dry and salty, with a very tough texture. When you eat it, it makes you want to chug a bottle of Vodka, which may just explain a lot. If you’ve ever been to Eastern Europe, you know what I’m talking about.